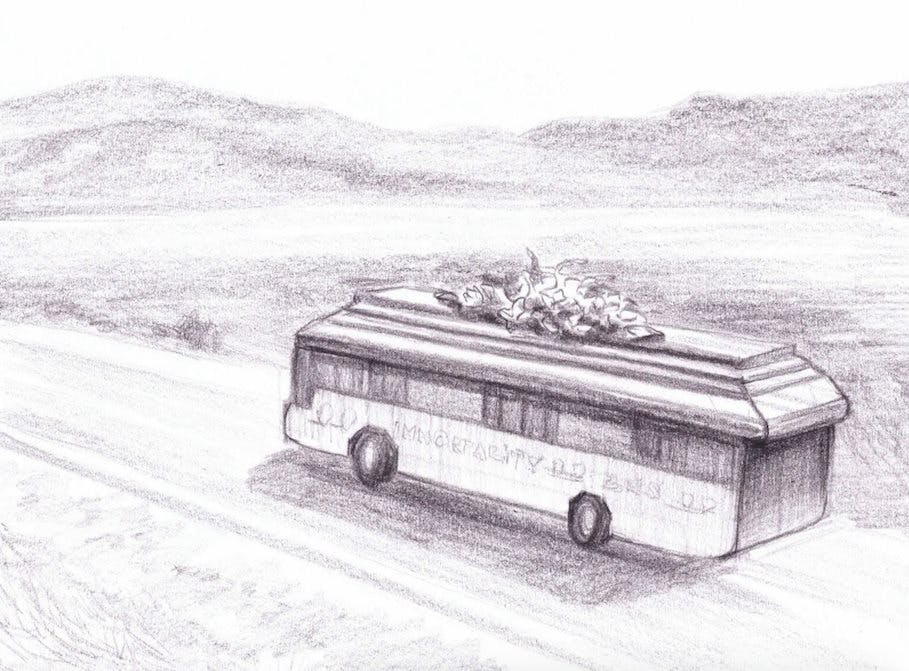

For Zoltan Istvan, the 2016 presidential election is a matter of life and death. The 41-year-old California native is campaigning across the country next month in a mobile, 40-foot casket—a less-than-subtle reminder of the future that awaits us all, unless we do something about first.

“The broadest point of my platform is that if you vote for me, support me, you’re really just supporting somebody who’s out for your own health. I’m trying to make it so people live a lot healthier and a lot longer,” Istvan told me recently as he was gearing up for his campaign trip. “When people talk about being the futurist president like Mr. Walker did, you have to laugh at that—a man who talks about the future in terms of Social Security and taxes. The future is not about these things. The future is about how technology is going to change the human species.”

Istvan is the founder of the Transhumanist Party, a new political ideology that wants to elevate the world’s rapidly developing technologies to the same political prominence as Social Security and taxes. On paper, Istvan actually looks like an ideal candidate. He’s 41, married, and a loving father of two girls. With cool blue eyes and only slightly graying hair, he even looks fit for office. He’s also a former Ivy League student of philosophy and religious studies, and the author of a novel called The Transhumanist Wager.

But the Transhumanist Party’s views are radical—even in the context of the headline-driven 2016 news cycle. Its political platform unfolds basically in three parts. First, it’s about enabling scientists and technologists to do everything they can to solve human death and aging. (Given proper resources, Istvan expects this could be accomplished within 15 to 20 years.) Second, the transhumanists want to develop a cultural mindset that embraces radical technology, and they want to create national and global safeguards that protect people against abusive technology and other perils we might face an a transhumanist era.

“I advocate for completely becoming a machine.”

Transhumanism suggests that the human race, on a long enough timeline, will use technology change what we think of as “human.” This means organ replacement, full limb replacement, and perhaps one day generating a computer model of your own human consciousness that might run for eternity somewhere. If machines can augment human capabilities enough, we may experience a type of immortality.

“I advocate for completely becoming a machine,” Istvan said. He suggests we’re in the midst of a philosophical and psychological shift toward mechanization. You can see the sprouts of this already; just look at how closely you keep your smartphone near your body. The next logical step is for the phone to literally be part of you, seamlessly augmenting your human capabilities. “The fact that we just jump on a jet airplane at 30,000 feet and don’t think anything about it is something already so transhuman in nature,” Istvan said.

If Istvan’s stump tour sounds like a massive PR stunt, that’s because it is.

The transhumanist mindset bridges a gap left impassable by other conventional political thinking, covering everything from artificial intelligence to immortality. It might sound so forward-thinking as to be obsolete, but there are signs of the future all around in us: in the DIY bodyhacking communities, where individuals are blurring the lines between man and machine, and in the progressive robotics being developed by MIT and Google’s Boston Dynamics. After all, we’re on the cusp of so-called designer babies, the ability to genetically modify DNA for beauty, health concerns, and intelligence at the point of conception. That’s exactly the sort of issue Istvan wants to force: It points to other not-far-off potential realities that ought to be planned for, or at least expected.

“What if we get to a point where we start to augment and improve intelligence? What if only rich people have access to it?” Istvan asked. “That’s not fair at all. You have to create policies around these things, and only third parties are willing to speak about this.”

Of course, most politicians wouldn’t touch that particular issue with a selfie stick.

It’s a “landmine,” Istvan said. “If Hillary Clinton was to come out and say ‘I support [designer babies],’ it would throw off the election in a very different way, and that’s what my goal is: to influence other politicians who might be willing to consider this thinking.”

But first, he needs to get his message out to the people. His “Immortality Bus,” which he describes as a “pro-science symbol of resistance against aging and death,” departs from San Francisco on Sept. 5, in what he intends to be a four-month-long tour—though he plans to do take every other week off to be with his family. The bus will feature the latest in high-tech gadgets: VR demos, drones, and most notably, an interactive robot (named Jethro Knights), which was funded—along with the rest of the trip—through an Indiegogo campaign that topped out at $25,375.

“Our first event is at a biohacking lab in the Mojave Desert,” he said. “I’m going to get a chip implanted in my hand.”

“What if we get to a point where we start to augment and improve intelligence? What if only rich people have access to it?”

The implant won’t be immediately useful, but it’s a precursor to the brain-implant technology that Istvan and his fellow transhumanists are anticipating. “I think that using electrical impulses [to stimulate the brain] is going to be a huge part of our future. Brain implants are not just about making violent criminals nicer; they might make you a better husband, a better wife, a better father.” (Scientists have found that electrical stimulation can improve learning and help improve reflexes and feelings of depression—which has led to a trend in “DIY brain hackers”—but far more research is still needed.)

Istvan is making it a point to not just preach to the transhumanist choir. The bus will venture to places like Mississippi, where the party’s ideas about the future may not be as familiar or as welcome as they are in Silicon Valley.

But the ultimate destination is Washington, D.C., where he plans to advocate for a drastically updated Constitution. Istvan intends to deliver a Cyborg Bill of Rights to Congress that addresses many issues the founding fathers could never have conceived of in our country’s formative years. “It makes no sense that we have a Constitution written about 300 years ago that [couldn’t conceive of] 3D-printed guns,” he said. “In three years, it’s going to be 3D-printed hand grenades and 3D-printed small nuclear devices.”

If Istvan’s stump tour sounds like a massive PR stunt, that’s because it is. He has no delusions about his campaign’s prospects and is plainly candid that he will not become president.

“As a presidential candidate—and I have no chance of winning and I think everyone knows that—we still speak about it as ‘what if,’” he said. “What if I was elected, then re-elected for another few years? What could I reasonably do within eight to 10 years?”

For now, Istvan genuinely believes he can help shape the the conversation about the technology policies of tomorrow.

“I have to convince people that third parties are how America became great,” he said. “It didn’t have two parties all along; that’s how it becomes stagnant. What it needs are new voices. Those voices don’t need to win. That’s something up to the popular vote.”

Illustration by Max Fleishman