When law enforcement needs help identifying locations for victims of sex trafficking, they turn to an unexpected source: Event and meeting planners. Now, the people that investigators turn to are empowering users around the U.S. to help fight sex trafficking.

Near the end of 2013, Molly Hackett and her colleagues at Nix, an event planning company in St. Louis, Missouri, received a call from law enforcement that would spark an idea for an application that uses image recognition to help find locations where minors are trafficked for sex. Knowing Hackett’s team was familiar with hotels, police asked them to identify a hotel room to ensure officers would be going to the right place.

Though police called on them and their peers with intimate knowledge of the travel and tourism industry to confirm locations before, Hackett says that it was this call that sparked the idea for TraffickCam, an identification database for locating instances of sex trafficking.

“When we hung up the phone, there were three meeting planners in the room, and we’re like ‘Holy smokes,’” Hackett said in an interview. “This was really the first time it dawned on us that meeting planners and Nix Conference and Meeting Management had a skill set that could help rescue children.”

Hackett and her colleague Kimberly Ritter established the Exchange Initiative, the group behind TraffickCam: an organization that works with different industries to raise awareness about child exploitation. The app is supported by a matching grant of $100,000 from the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph.

The app helps streamline investigations into sex trafficking and the exploitation of minors, which law enforcement is fighting across the U.S. In 2016, 1,654 cases of human trafficking have been reported, according to the National Human Trafficking Resource Center, and the majority of those cases are sex trafficking. The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children said in 2014 that one in six endangered runaways reported to the organization were likely sex trafficking victims.

Abby Stylianou, computer vision researcher at Washington University in St. Louis’s Media and Machines Lab partnered with Hackett and Ritter to build the app they’d envisioned after she learned about the project during her time in the FBI Citizen’s Academy.

Stylianou previously worked with law enforcement to use image recognition techniques and find the decades-old remains of a young murder victim in 2013. Along with Media and Machines Lab cofounder Robert Pless, Stylianou created the photo-matching app.

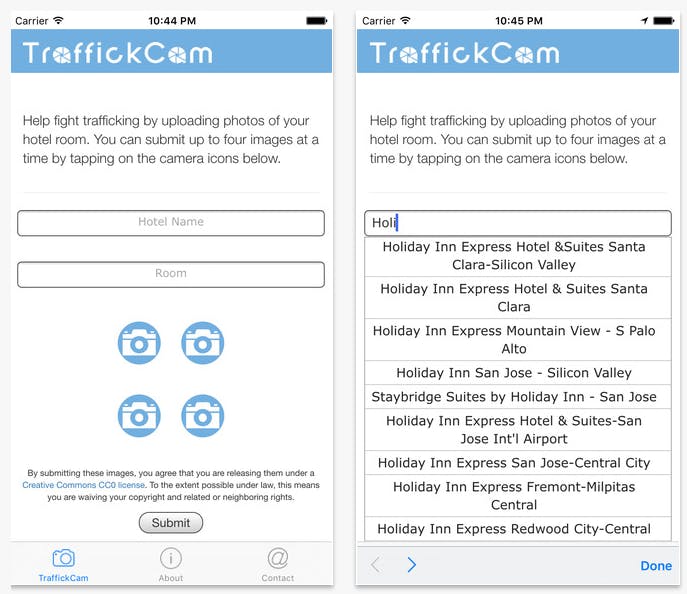

All it takes is four photos. By snapping pictures of your hotel room and sharing it with TraffickCam, you can help law enforcement identify the locations of where minors are sex trafficked. It’s available on iOS, Android, and on the web.

When you get to the room in your hotel, take photos of it in its untouched condition. Then upload them to the app with information about the hotel and location. When someone wants to identify a photo of a potential victim, the app will cross-reference your photos with those submitted through the law enforcement portal to see if it can find a match to carpeting, wall art, or other recognizable features of the photos. Law enforcement will receive a list of potential results in order of most probable locations.

“This works really nicely for hotel rooms where you might have a piece of art that’s the same piece of art even if the walls are panted a different color and there’s a different cover on the bed. We can pick up on these things that are similar,” Stylianou said in an interview.

The data collection and matching process works by extracting features from your photos—like carpet, curtains, or bed sheets—and assigning these unique textures a numerical representation. On the law enforcement side, an image is uploaded and, after the software masks sensitive content, it extracts the same set of features and tries to align images with similar unique textures, Stylianou explained.

Already, the app hosts 1.5 million images, some uploaded from hotel websites and others from users of the app. As the database grows, the app will use a different technique that can handle millions of images, identifying and matching similar feature groups instead of individual features. Researchers will also try implementing machine learning techniques to improve accuracy.

No personal data is stored or sent through the app; it’s all reported anonymously, and any photos with people are eliminated from the database. The automatic identification on the law enforcement side is still in beta among agencies in St. Louis county, but early tests are encouraging: There’s an 85 percent accuracy in returning the correct hotel within the first 20 images.

Though the technology is promising, its potential could be seen as worrisome. Although only law enforcement can access the image-matching database, the app relies on the trust of those in power to not disabuse the resource. For instance, there are no measures to block law enforcement from searching any photo, including sex workers who are not involved in trafficking, or anyone else in a hotel room.

Stylianou said she shared similar concerns early on in the project, and made it clear that the app is only for focusing on victims of sex trafficking.

“This is something that Robert and I are very cognizant of,” she said. “We hesitated early on how involved we wanted to get with this because we were worried this was going to end up primarily being used to fight sex work as opposed to fighting sex trafficking. That’s just not the problem domain we want to work on.”

After speaking with Sgt. Adam Kavanagh at the St. Louis County Police Department, Stylianou said she felt much more comfortable moving forward with the project, as he reassured her the work being done was solely targeting minor victims of sex trafficking, not prostitution.

“It’s something we’re still aware of as we develop the application and it’s certainly the reason that the backend portal will only ever be accessible to provisioned members of law enforcement,” she said.

By using the app, you are placing your trust in law enforcement agencies to not abuse tools that use recognition software to identify locations of individuals. The photo recognition capabilities are planning to roll out across the U.S. later this year.

Beyond law enforcement partnerships, researchers at the Media and Machines Lab are continuing to explore other opportunities for computer vision as a tool for social good, from citizen journalism to identifying how quickly and properly plants grow.

Since launching the Android app last week and ramping up attention for the TraffickCam, popularity is exploding. People are downloading the service and uploading photos from hotel rooms around the country.

All it takes is a few moments to capture the stillness of your hotel room before you get settled in. Those four snapshots could potentially help law enforcement track down exploited young people faster than ever.

H/T The St. Louis Post-Dispatch | Photo via Pete O’Shea/Flickr (CC by 2.0) | Remix by Max Fleishman