With the release of iOS 9.3, Apple is introducing a feature called Night Shift. Once the update is officially rolled out, devices running the latest version of the company’s mobile OS will have the option of automatically shifting display colors to the warmer end of the spectrum after sunset, making the screen easier on the eyes in the wee hours of the night.

Night Shift will likely become a favorite feature of iOS users, and Apple is well aware—it borrowed the functionality from a popular third-party that did the exact same thing.

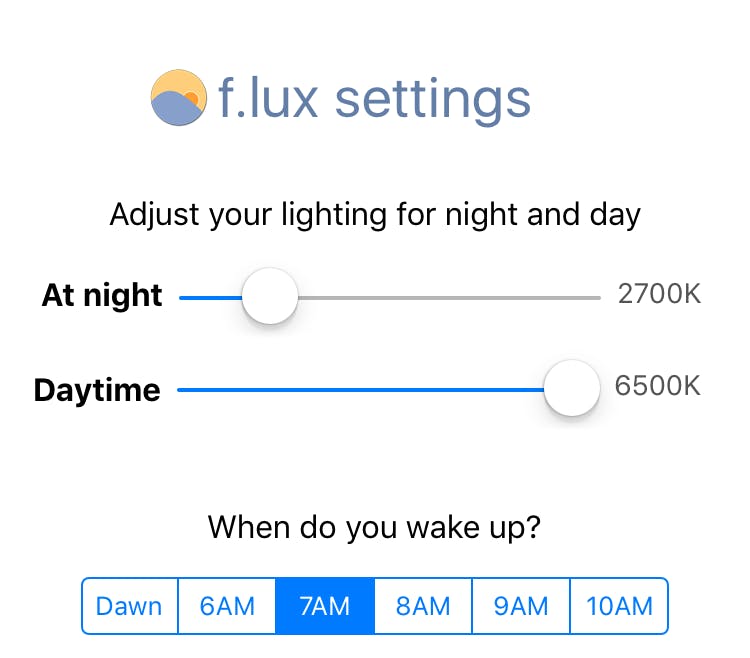

F.lux has been making computer and phone displays easier on the eyes since 2009. With research showing that the blue light emanating from screens was making it harder for people to fall asleep at night, developers (and husband and wife) Michael and Lorna Herf crafted the app to adjust color temperature and reduced eye strain. The desktop version of the app has been downloaded over 15 million times to date.

To be clear: F.lux isn’t the only piece of software that attempts to mitigate the effects of blue light at night, but it’s easily the most well known and universally considered to be the most user-friendly. It also has the biggest footprint across virtually all platforms, including both desktop and mobile.

In 2011, f.lux made its way to iOS, albeit only for jailbroken devices. Earlier this year, Apple began allowing sideloading—installing apps not from the official App Store—to users willing to download Apple’s Xcode developer tools and create a free developer account. F.lux was made available through this somewhat tedious process and according to the developers, the page explaining how to install the app was visited 176,000 times in the first 24 hours.

In November 2015, Apple blocked further installations of f.lux because, according to the Cupertino company, the app violated the Developer Program Agreement.

Rumors started swirling as to why Apple would kill off the beloved app, though the company line that f.lux’s use of private APIs breaks Apple’s rules—something that the developers hold was necessary for their app to work.

“[F].lux cannot ship an iOS App using the Documented APIs, because the APIs we use are not there. In the last 5 years, we have had numerous conversations with Apple about our product and what would be required to make it work with iOS,” the developers explained on their website.

Despite an online petition calling for approval of f.lux for iOS racking up over 5,000 signatures and nearly 2,000 comments, Apple has remained steadfast in blocking the app on its mobile platform.

The reason now seems obvious: Night Shift, Apple’s own version of f.lux that operates on the exact same principles and addresses the exact same issue. Millions of iPhone and iPad owners will get the functionality of f.lux without ever knowing it existed, and the developers will have to shift focus to other platforms and wave the white flag on the battle for iOS.

You’ve been Sherlocked

Herf saw the writing on the wall after f.lux got the boot from iOS. In November 2015, he told Re/Code, “Their new devices — 6s, 6s Plus — they’ve put in some color-matching features in the phones, but they don’t change their screen color. When you poke around in their APIs, it’s not a big leap to say they’re thinking about the topic.”

This isn’t the first time a third-party developer has seen its functionality absorbed by Apple without so much as a hat tip for the idea. It happens with such regularity that it has its own term: “Sherlock.” When an app that is essentially made obsolete by Apple making its own version of the service, it’s said to have been Sherlocked.

The term dates back to 2002, when Apple issued an update to its native OS X app Sherlock that included functionality extremely similar to that of a third-party competing program developed by Karelia Software known as Watson. While Watson was originally built to serve as an extension or companion to Sherlock 2.0, Apple essentially appropriated all the features of the app into version 3.0 of its own product. By 2004, Karelia discontinued Watson—but not before selling it to Sun Microsystems.

In a blog post revisiting the situation, Karelia founder Dan Wood spoke about his experiences. After contacting Apple Developer Relations and expressing his displeasure, Wood wrote that he received a call from Steve Jobs. “‘Here’s how I see it,’ Jobs said — I’m loosely paraphrasing. ‘You know those handcars, the little machines that people stand on and pump to move along on the train tracks? That’s Karelia. Apple is the steam train that owns the tracks.’”

Apple takes a bite out of developers

It has become annual tradition during the Apple Worldwide Developers Conference (WWDC) for developers and press to recount all of the programs that get Sherlocked.

In many cases, it doesn’t end up doing all that much damage. While Apple can better integrate its own programs into the overall iOS ecosystem, the reveal of first-party programs doesn’t guarantee death for third-party competitors; Google Maps has continued despite Apple ditching it for its own Maps app and read-later apps like Instapaper and Pocket haven’t disappeared despite the introduction of Reading List.

Apple often drives people to alternatives when it rolls out its own applications, especially when those apps are designed to be more straight-forward and less friendly to power users.

Better yet for third-party developers is when Apple’s apps just straight up don’t work as designed, as was the case early on with the Podcasts app. Instead of killing off the market, Apple bolstered it by bungling their own products and pushing users to alternatives.

Of course, Apple is more likely to hit than to miss when it decides to create an app of its own. If that’s the case, developers just have to deal with it; there isn’t much option for recourse.

“Anyone in the business of creating utilities for OS X/iOS should assume that Apple might copy their app’s functionality at any time,” a Mac Developer, who asked to remain anonymous, told the Daily Dot. “If they do, there’s nothing the developer can really do – it’d take a huge army of lawyers to go after Apple, and if your app does something that might be deemed basic functionality, you’d probably lose anyway.”

Getting f.luxed

The difference between many of the apps that have previously been Sherlocked and what has happened to f.lux is the tilt of the playing field. Apple is always at an advantage, but a third-party program at least has a shot when it’s available in the App Store.

F.lux, on the other hand, has effectively been shut out completely by Apple, both in an official capacity and through alternative methods. While the developers of f.lux have continued to insist their willingness to work with Apple to get the app on iOS, they have had no such luck.

“They should just move on,” the anonymous developer said. “Changing color schemes by time of day seems like a system-level feature…Unfortunately for F.lux, this isn’t a fight they can take on (as they couldn’t ever do this on iOS anyway), nor if they could, one they’d be likely to win.”

The developer said the introduction of Night Shift is bad for f.lux, but it’s good for iOS users; they get the benefit of the extraordinarily helpful function provided by f.lux built right into their devices.

Night Shift doesn’t necessarily spell death for f.lux on iOS—the app can still be installed on jailbroken devices, and because Night Shift will be available only for 64-bit devices, older iPhones and iPads will only be able to get the color warming effect through alternatives like f.lux. And, of course, there will always be those 15 million folks who count on f.lux to keep their computer screens visible late into the evening.

It likely isn’t much comfort for the creators of f.lux, but if it’s true that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, they should be extremely flattered.

Photo via Thangaraj Kumaravel/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) | Remix by Jason Reed