Whistleblower Edward Snowden‘s revelation early this month that U.S. intelligence agencies have been gathering user data directly from nine of the largest Internet companies in the U.S.—including Google and Facebook—shocked many Americans.

But, considering the history of the NSA, maybe it shouldn’t have. Decades before the agency was collecting massive amounts of phone and Internet records, it was collecting telegraph records in an operation that raises similar legal issues and worries about lack of oversight.

In August of 1945, U.S. Army representatives met in secret with the country’s three major telegraph companies, ITT World International, RCA Global, and Western Union. They explained that the Army Signal Security Agency wanted copies of all telegrams sent to and from the United States. World War II was coming to a close and the top secret, multinational Manhattan project had proven the power of foreign intelligence. Executives from the three companies agreed to comply, provided they were assured by then-Attorney General Tom Clark that it was not illegal for them to do so. There is no record any such assurance was officially given, but the operation went ahead anyway.

With that, the organization that became the National Security Agency—the “No Such Agency”—launched its first large-scale domestic surveillance project and set out establishing the policies and practices that would one day produce PRISM.

The telegraph operation, codenamed SHAMROCK, was a massive undertaking in the time before digital data storage: Once a day, beginning in late 1945, the Army sent couriers to telegraph offices in New York; Washington, D.C.; San Francisco; and San Antonio to pick up all their international telegrams—which were stored at first on hole-punched paper and later on reels of magnetic tape. Analysts then sifted through the communiques, looking for encrypted intelligence and evidence of Soviet spying.

The Army’s concern was not without justification. By the time SHAMROCK was underway, the Soviets were aggressively pursuing an atomic weapon. The project was fueled by “atomic spies” such as the infamous Morris Cohen, who, in cooperation with an unknown Los Alamos scientist, sent the Soviet Union detailed blueprints of America’s first nuclear bomb only 12 days before it was successfully detonated in the Trinity test. “Stalin ordered a crash program and exploded a similar atomic device four years later,” wrote the New York Times.

Nevertheless, the telegraph companies continued to worry over the legality of their participation in SHAMROCK. They asked for guarantees from the president, the Department of Defense, and the attorney general that they would not be prosecuted. A memo in 1947 indicated that they apparently got it (albeit under the table and with the caveat that future administrations would not be bound to uphold the commitment).

According to a report by L. Britt Snider, a congressional investigator who examined SHAMROCK in the 1970s, “documents showed that Secretary Forrestal in June 1948 quietly tried to have Congress amend Section 605 of the Communications Act of 1934 in a way which would have made the companies’ cooperation in SHAMROCK clearly legal.” Section 605 prohibited telegraph companies from divulging the information contained in the telegrams they processed. Snider wrote that Forrestal “met informally with the Chairmen of the Senate and House Judiciary Committees to explain the situation, and an amendment was drafted to accomplish the objective.” But the amendment was never carried out.

By 1949, the program was being run by the Armed Forces Security Agency. When, a few years later, under Truman’s administration, the AFSA was folded into the newly-formed NSA, the legal ambiguities surrounding SHAMROCK persisted: “There was little consultation with General Counsel on what were perceived to be policy matters,” wrote James Hudac, a retired NSA senior executive. “In its early years, the late 1950s, NSA had a single ‘legal adviser’ who, according to at least one story, had so little to do he arranged to have his position abolished so he could retire.”

For the next two decades the program continued in secret, often even from the top staff of the NSA. In an interview that Snider conducted with Louis Tordella, the Deputy Director of the agency from the late 50s until 1974, “Tordella recalled that years would sometimes go by without his hearing anything about SHAMROCK. It just ran on, he said, without a great deal of attention from anyone.” Snider added:

I asked if NSA used the take from SHAMROCK to spy on the international communications of American citizens. Tordella responded, “Not per se.” NSA was not interested in these kinds of communications as a rule, he said, but he said there were a few cases where the names of American citizens had been used by NSA to select out their international communications, and to the extent this was done, the take from SHAMROCK would also have been sorted in accordance with these criteria…When I asked if it was legal for NSA to read the telegrams of American citizens, he replied, “You’ll have to ask the lawyers.”

In a study of the agency, NSA historian Thomas Johnson wrote that, during the height of the Cold War, the NSA was engaged in wiretapping and watch-list operations that it “seemed to understand [were] disreputable if not outright illegal.” The years surrounding the Cuban Missile Crisis–when the NSA was still relatively new–were a time of profound mistrust. And the importance of secrecy and foreign intelligence couldn’t be overstated as the Soviet Union and the U.S. amassed enough atomic weapons to accomplish their mutually assured destruction. (By 1965, the U.S. alone had more that 30,000 nuclear warheads.) Legality, in this context, was no doubt considered a secondary concern. “I noted [to Tordella] I would have expected the companies themselves to be concerned,” wrote Snider, “and Tordella remarked that…whatever they did, they did out of patriotic reasons. They had presumed NSA wanted the tapes to look for foreign intelligence.”

Questions over the legitimacy of SHAMROCK cropped up again when, in 1967, the Supreme Court ruled that the Fourth Amendment—which protects against warrantless searches and seizures—did apply to communications in which a reasonable expectation of privacy could be assumed. The ruling, however, avoided addressing issues of national security. “There was occasional, continuing concern that the president’s constitutional authority to conduct electronic surveillance for foreign intelligence purposes might be subject to challenge,” Hudac wrote. When the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 was passed, a provision was added which stated that, “nothing contained in this chapter or in section 605 of the Communications Act of 1934 shall limit the constitutional powers of the president…to obtain foreign intelligence information deemed essential to the Security of the United States.”

Thus, concluded Hudac, “a collection activity such as SHAMROCK was no longer subject to the warrant requirements or constraints of those two acts.”

In the 1970s, tensions between the Soviet Union and the U.S. relaxed as the two nations settled into a period of détente. The NSA’s budget was slashed. Around that time, a series of scandals prompted new inquiries into U.S. intelligence gathering practices: First, in 1970, an Army officer disclosed that the Army had plainclothes soldiers embedded in civilian protests. Two years later, the Watergate scandal broke. It was followed, in 1974, by the leaking of a massive report of covert CIA activities to the New York Times. The report, which CIA director William Colby referred to as “skeletons in the closet” of the agency, showed that the CIA opened mail going to and from the Soviet Union and China, plotted the assassinations of foreign leaders, and wiretapped journalists—an action apparently authorized by then defense secretary Robert McNamara.

As a result, a Senate Committee led by Frank Church was formed to conduct an investigation of the government’s intelligence gathering activities, among them SHAMROCK. At the NSA, Hudac wrote, “efforts were underway within the executive branch to bring to a close certain activities which were to become the primary subjects of those inquiries…Questions had arisen earlier concerning unrelated electronic surveillance conducted by the White House staff as well as certain support provided to the White House by various federal agencies.”

In May of 1975, after the New York Times published an expose on SHAMROCK, the defense secretary ordered the project shut down. When Snider asked him if the massive 30 year domestic surveillance operation was terminated because of the Church Committee, Tordello replied: “Not really…the program just wasn’t producing very much of value.”

The Church Committee—which later became the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence–went on to publish fourteen reports on U.S. intelligence gathering techniques. Their investigation into SHAMROCK spurred the passing of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) in 1978, establishing a protocol for electronic surveillance.

It is this act that became the subject of debate in 2006, when USA Today reported that the NSA had, since September 11, 2001, been “secretly collecting the phone call records of tens of millions of Americans, using data provided by AT&T, Verizon and BellSouth.”

In the post Cold War years, the new justification for large-scale domestic spying operations had become thwarting terrorist organizations such as al-Qaeda—which, in fact, had emerged from a U.S.-armed resistance group during the Soviet war in Afghanistan between 1979 to 1989. The White House’s deputy press secretary Dana Perino told the paper the NSA’s phone call surveillance was “necessary and required, for the pursuit of al-Qaeda and affiliated terrorists.”

According to Perino, because the call database was a matter of national security, the agency’s actions were legal. Presumably the NSA was protected by the Omnibus Crime Control Act of 1968. But it was unclear whether the same was true for the telecommunications companies who shared their customers’ information.

The ACLU filed a lawsuits against AT&T and Verizon on behalf of 100,000 of its members (including a former AFSA linguist). Two years later, however, Congress passed an amendment to FISA in 2008 stating that, “a civil action may not lie or be maintained in a Federal or State court against any person for providing assistance to an element of the intelligence community.” The legislation granted this immunity retroactively to any past telecommunications companies that had aided the government. In essence, it was the legal assurance that the telegraph companies sought during SHAMROCK–protection for sharing citizens’ private communications with large-scale NSA surveillance projects. The ACLU case was dismissed in 2009.

This 2008 amendment to FISA now protects Silicon Valley companies like Google and Facebook, who provide the NSA’s Internet surveillance program, PRISM, with their customers’ emails, chats, videos, and other communications.

Set to expire at the end of 2012, an extension of the amendment was debated in Congress late last year. Among the debaters was Colorado Senator Mark Udall. A member of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence–the successor of the Church Committee–Udall was aware of PRISM, the Washington Post reported, but was bound by oath not to speak of it directly. “As it is written,” Udall warned the Senate, “there is nothing to prohibit the intelligence community from searching through a pile of communications, which may have been incidentally or accidentally been collected without a warrant, to deliberately search for the phone calls or emails of specific Americans.”

Also a member of the Senate Intelligence Committee, Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden found himself in a similar position. “Wyden repeatedly asked the NSA to estimate the number of Americans whose communications had been incidentally collected,” the Post wrote. “Eventually Inspector General I Charles McCullough III wrote Wyden a letter stating that it would violate the privacy of Americans in NSA data banks to try to estimate their number.”

On Dec. 29, 2012, Congress approved a five-year extension of the FISA amendment.

Years after the Cold War ended, former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara gave an interview to historian Richard Rhodes in which he reflected on the era of nuclear buildup, surveillance, espionage, McCarthyism and proxy wars that defined the second half of the 20th century: “Each individual decision along the way seemed rational at the time,” he said. “But the result was insane.”

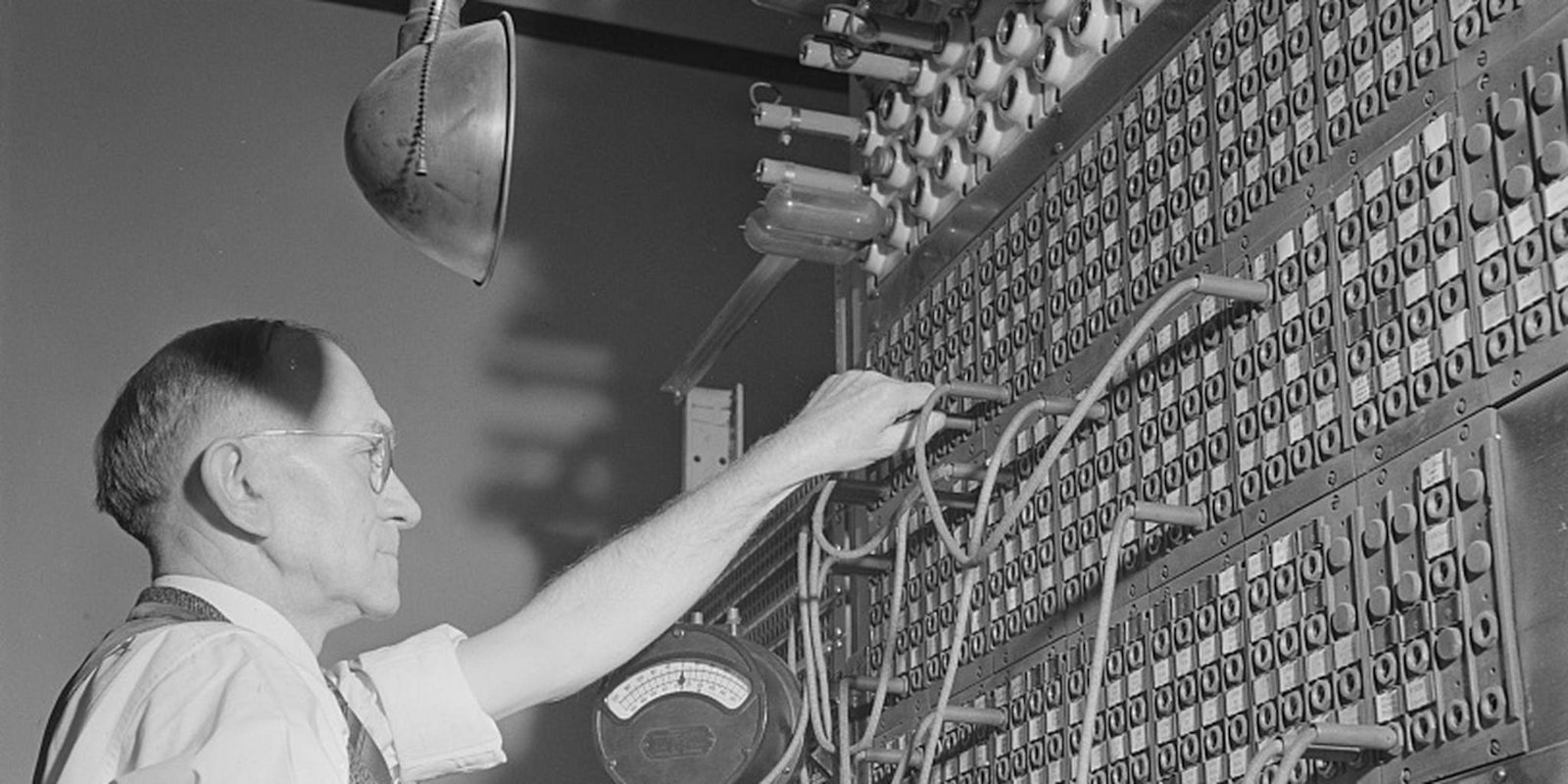

Photo by Jack Delano/Library of Congress