A Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) informant targeted more than two dozen countries in a series of high-profile cyberattacks in 2012. The names of many of those countries have remained secret, under seal by a court order—until now.

A cache of leaked IRC chat logs and other documents obtained by the Daily Dot reveals the 30 countries—including U.S. partners, such as the United Kingdom and Australia—tied to cyberattacks carried out under the direction of Hector Xavier Monsegur, better known as Sabu, who served as an FBI informant at the time of the attacks.

The actual attacks were carried out by highly skilled hacktivist Jeremy Hammond, who broke into countless international websites identified by his partner, Monsegur. At the time, Hammond was unaware that Monsegur was working as an FBI informant. Hammond was arrested in March 2012 on charges based largely on information provided by the man he knew as Sabu.

Amassed by federal agents with direct access to communications between Anonymous hacktivists, the private correspondence of Hammond and Monsegur, cofounder of hacktivist crew LulzSec, reveals the facilities of the AntiSec hacking group, who, under the FBI’s constant surveillance, launched successive cyberattacks against foreign government networks.

FROM MOTHERBOARD:

How an FBI informant helped orchestrate the hack of an FBI contractor

Databases containing the login credentials, financial details, and private emails of foreign citizens, and in some cases government agents, were exfiltrated by hackers tasked by Monsegur to do as much damage as possible. At Monsegur’s instruction, the stolen data was routinely uploaded to a server under the FBI’s control, according to court statements.

The names of countries involved in these attacks remain redacted by order of Judge Loretta A. Preska of the U.S. District Court in Manhattan. However, a sentencing memorandum filed last year reveals that Hammond’s attorneys, Susan G. Kellman and Sarah Kunstler, believed the criminal nature of Monsegur’s undercover activities warranted closer scrutiny by the court.

“Why was our government, which presumably controlled Mr. Monsegur during this period, using Jeremy Hammond to collect information regarding the vulnerabilities of foreign government websites and in some cases, disabling them,” Hammond’s attorneys wrote in December 2013.

“This question is especially relevant today, amidst near daily public revelations about government’s efforts, worldwide, to monitor the communications of, and gather intelligence on, world leaders.”

Two weeks after the memorandum was filed, Preska sentenced Hammond to 10 years behind bars, the maximum allowed under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. Monsegur, however, walked free in May with a year of probation after having served only seven months in jail for communicating with Anonymous. Preska, who also ruled over Monsegur’s case, and the U.S. Attorney’s office praised Monsegur for his role in Hammond’s conviction.

The FBI refused to comment on Hammond’s case or Monsegur’s involvement as an informant, saying only that the agency adheres strictly to the U.S. Attorney General’s guidelines.

The 94-page memorandum from Hammond’s legal team was eventually published in April 2014 by the document-leaks website Cryptome. It contains a summary of discovery materials—evidence collected by the FBI against Hammond—that details Monsegur’s integral role in a slew of computer crimes. Due to the protective court order, however, the names of all foreign countries involved in the 2012 cyberattacks were all carefully blacked out.

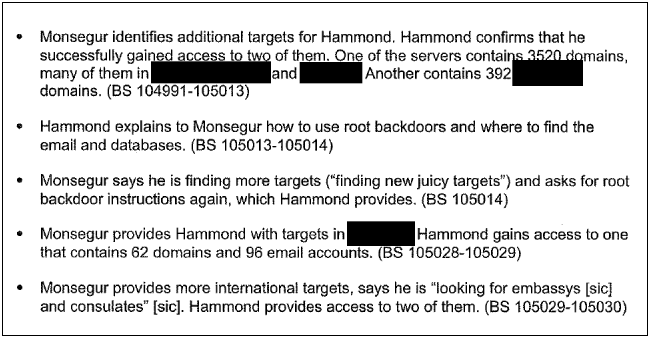

A section of Kellman and Kunstler’s letter, redacted by the court.

The names of several countries allegedly targeted by Monsegur have been published by major news sources in the past, including the New York Times, which listed the names of six countries in an article published last April.

A joint investigation this summer by the Daily Dot and Motherboard further revealed that Monsegur ordered fellow hackers to deface government websites and steal confidential information from servers in Turkey and Brazil, according to sealed court documents leaked to the reporters. Additionally, Monsegur played a crucial role in staging high-profile cyberattacks against FBI security contractor ManTech, and the Texas intelligence firm Stratfor, the latter of which suffered an estimated $3.78 million in damages as a result of the breach.

READ MORE:

FBI informant led cyberattacks on Turkey’s government

Below is an unredacted version of Hammond’s sentencing memorandum drafted by the Daily Dot. Although the original document was unavailable, leaked chat logs, which correspond to the bates numbers cited next to each bullet point, identify the names of the countries censored by the court.

This is the first time this information has been made public.

Note: Text in yellow indicates the names previously redacted from the court document. Click on the linked “BS” numbers to view the corresponding chat logs between Monsegur (“leondavidson“) and Hammond (“yohoho”), which were used by the Daily Dot to un-redact the names.

Discovery timeline pertaining to hacks of foreign websites

Jan. 23, 2012:

• Mr. Monsegur gives Mr. Hammond a list of Brazil targets with Plesk vulnerabilities and asks him to “hit these… for our brazilian squad.” (BS 104988 – 104989)

• Hammond hacks one of these targets and shows Monsegur the site contains 287 domains and 1330 different email accounts. Monsegur says he will give these targets to Brazillian hacker “Hivitja” (actually Havittaja) to hack the sites. Monsegur tells Hammond to create a root backdoor (“just backdoor urls”) so the sites can be accessed again. Hammond also gives Monsegur passwords for some of the sites. (BS 104989 – 104990)

• Monsegur identifies additional targets for Hammond. Hammond confirms that he successfully gained access to two of them. One of the servers contains 3520 domains, many of them in Netherlands and Belgium. Another contains 392 Brazil domains. (BS 104991 – 105013)

• Hammond explains to Monsegur how to use root backdoors and where to find the emails and databases. (BS 105013 – 105014)

• Monsegur says he is finding more targets (“finding new juicy targets”) and asks for root backdoor instructions again, which Hammond provides. (BS 105014)

• Monsegur provides Hammond with targets in Slovenia. Hammond gains access to one that contains 62 domains and 96 email accounts. (BS 105028 – 105029)

• Monsegur provides more international targets and says he is “looking for embassies [sic] and consulates” [sic]. Hammond provides access to two of them. (BS 105029 – 105030)

• Monsegur asks Hammond to access a Brazil site, but he is unable to gain access. (BS 105041)

• Monsegur gives Hammond more Brazil targets, including Globo, which he describes as a “big target.” Hammond provides passwords. (BS 105041 – 105042)

• Monsegur provides more Brazil targets. Hammond gains access to one of them and provides the password, as requested. (BS 105044-105046)

• Monsegur provides a long list of targets from many different international countries including United Kingdom, Australia, Papua New Guinea, Republic of Maldives, Philippines, Laos, Libya, Turkey, Sudan, India, Malaysia, South Africa, Yemen, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Trinidad and Tobago, Lebanon, Kuwait, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Argentina (BS 105061-105063)

• Monsegur tells Hammond that he will give the Turkey government sites to a Turkish hacking group known as RedHack (“the .gov.tr’s will be handled Redhack famous Turkish hackers”) and tells Hammond that the sites he has given him are “high priority”—as if he were placing an order. (BS 105063)

• Monsegur invites Hammond to the RedHack channel so Hammond can provide the Turkey sites (“accept invite”). Monsegur also provides more Turkish domains (BS 105065 – 105066)

• Hammond tells Monsegur that one of the servers has mail for 22 Turkey government domains and another has mail for about 600 domains. (BS 105067)

• Monsegur creates a chat room and invites Hammond and an alleged member of RedHack. They exchange information regarding thousands of Turkey sites. (BS 62889)

• Hammond explains to the alleged Redhack member how to access the root backdoors of the Turkey sites. (BS 62889-62897)

Jan 26, 2012:

• Monsegur follows up on foreign government targets he provided Hammond “last night.” Hammond sends back a list of the sites he did not gain access to, including government sites in Libya, Yemen, Sudan, Philippines, Iran, and United Kingdom. (BS 105077-105078)

• Monsegur asks for the list again. Monsegur again asks for instructions on how to access root backdoors. Hammond gives Monsegur the information. (BS 105080-105081)

• Monsegur provides more Iran targets to which he wants access. (Monsegur: “lend me an hour of your time to bang out these Iranian targets.”) Hammond gains access to one that hosts seven domains and 56 email accounts. (BS 105091)

• Monsegur provides two targets in India. Hammond cannot gain access to either. (BS 105091 – 105092)

Feb 2, 2012:

• Monsegur provides more targets, including a government site in United States and government sites in Nigeria, Republic of Maldives, Paraguay, Saint Lucia, and Puerto Rico. Mr Monsegur asks again for instructions on how to access root backdoors. (BS 67554)

• Monsegur provides targets in Greece, United Kingdom, and Turkey. Hammond accesses one of the Greece sites that contains 135 domains and 287 email accounts. (BS 67559 – 67561)

Feb 15, 2012:

• Monsegur provides targets in Slovenia. He tells Hammond that these sites are for “tony, the guy who hacked kingcope.” (BS 105191)

• Monsegur tells Hammond he is “setting up a new box to serve as another for onion for us as a third backup” and says, “I want us to have redundant backups for all our shit.” (BS 105192-105193)

• Hammond provides access to some of the Slovenian sites. He creates three backdoors and tells Monsegur that they contain hundreds of domains and emails. Hammond comments “hopefully were getting something out of all this.” Monsegur responds, “trust me…everything i do serves a purpose ;P” (BS 105195)

• • •

Update 11:54am ET, Oct. 2: The FBI has refused to comment on any aspect of Jeremy Hammond’s case.

Subscribe to the Daily Dot Politics newsletter here, and follow us on Twitter at @DotPolitics.

Photo via Joseph McKinley/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) | Photo by Brian Knappenberger | Remix by Rob Price