BY LISA KNISELY

When I am not writing, I am teaching courses at the college level on gender and feminist theory. One of the first and most important things I try to teach students in my courses is to always do a generous reading of whatever we happen to be reading in class for the day. By “generous reading,” I mean that I tell my students that they should try to understand an argument first using the groundwork laid out by the person making the argument—even, or perhaps especially, if they disagree with that argument. Once they’ve done the generous reading, I advise them, then they can go ahead and try to rip the argument to shreds if they disagree with it.

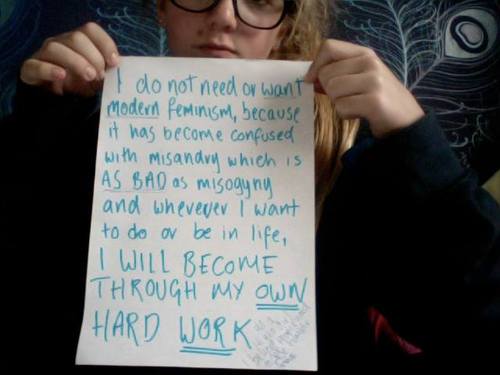

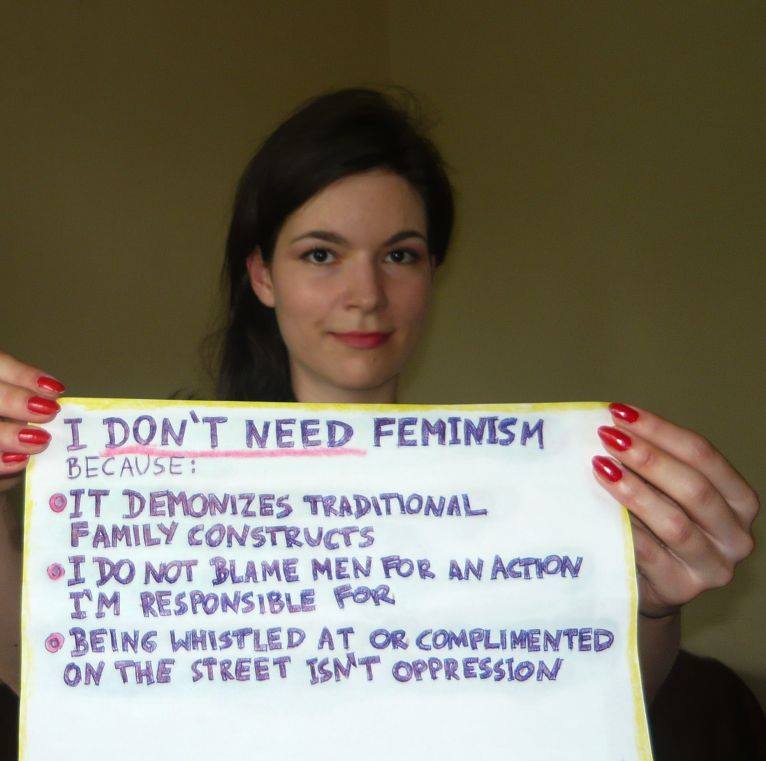

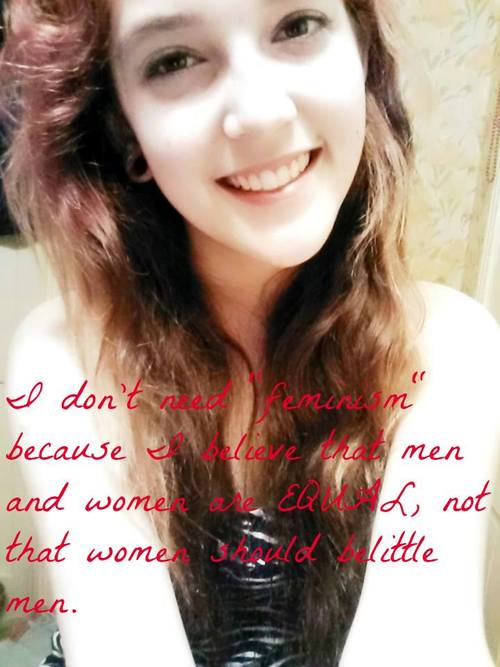

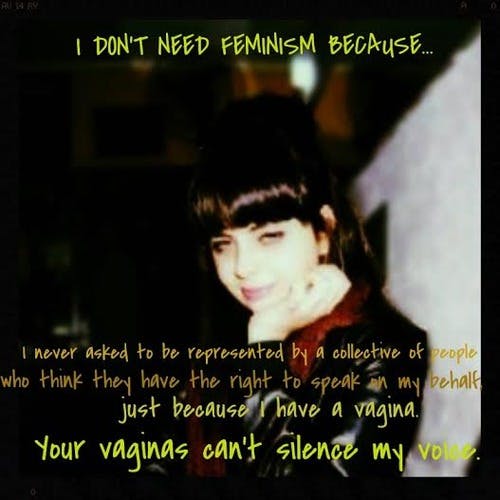

So, when I first got wind of the Women Against Feminism social media meme and its corresponding Tumblr, I was forced to take my own advice and try to understand what it was that these women were trying to say on their own terms. I’m not going to lie to you—as an avid and unapologetic feminist, it wasn’t easy. However, once I forced myself to do it, I found that some of the points brought up by the women of Women Against Feminism were actually pretty similar to some of the points many feminists have been making about feminism, too.

Sure, it was obvious that a lot of the content of Women Against Feminism is based on ignorance and misinformation about feminism borne out of backlash rhetoric. As Allegra Ringo points out over at Vice.com (not exactly a paragon of feminist journalism itself), there seems to be a lot of undue emphasis on whether or not it is feminist or not for men to open jars for women.

This is just one indication that the women of the Women Against Feminism are largely missing the most pressing and relevant political aspects of the feminist movement.

Despite this, I have still been a little troubled by some of the dismissive (if still hilariously witty) responses that have been aimed at Women Against Feminism. It’s almost as if feminists have forgotten that we have been arguing internally, sometimes quite bitterly, about what feminism is ourselves for decades.

This disagreement is necessary and vital if feminism doesn’t want to become the self-righteous, moralizing movement that anti-feminists accuse it of being. There is something to be learned from Women Against Feminism, even if the lesson isn’t an easy one.

While there are plenty of posts worthy of nothing more than an eye roll, Women Against Feminism can act as an important reminder for feminists that we don’t have everything figured out just yet (and we probably never will, either). For example, one entry on the Tumblr reads “I don’t need feminism because #yesallwomen have [sic] no right to speak for me!”

Grammar aside, this is an essential point many feminists have been making for years and years: you can’t lump all women into one singular category because not all women are the same. Attempts to speak for “all women” are often exclusionary and misrepresent the lived diversity of women’s lives.

While the #yesallwomen hashtag on Twitter has been a powerful mobilizing and consciousness-raising tool, it is still completely legitimate to critique the idea that all women have the same experiences, interests, or politics—or that they ought to. Talking about “all women” in the name of feminism should be suspect, as many feminists are quick to point out.

Another post begins, “I don’t need feminism because feminism is a predominately white middle-class movement.” This, too, has been a point of contention for the feminist movement since at least the so-called “First Wave” of feminism when white suffragettes used racist and xenophobic rhetoric to try to justify gaining the right to vote for white women.

While it would be very inaccurate to say that only white, middle-class women are feminists, the feminist movement has always had a problem with racism, classism, and other forms of discrimination within its ranks. As many feminists acknowledge, it is at our own peril to ignore this fact. If some women choose not to identify as feminists because they feel that feminism participates in other forms of oppression, that is also a completely legitimate critique of feminist politics worthy of our attention, not our dismissal.

Another place where some feminists might be inclined to agree with the women of Women Against Feminism is on a point brought up by women in multiple posts. One woman’s sign reads: “I don’t need feminism because it reinforces the men as agents/women as victims dichotomy.”

While a good deal of feminist activism has been quite obviously about combating the “men as agents/women as victims dichotomy,” plenty of feminists have also worried amongst ourselves whether we weren’t also sometimes unintentionally reinforcing that binary with our own political and legal strategies, such as in the enactment of some sexual harassment law and policy.

Even if feminism has also been very actively about making women’s victimization visible, such as fighting to change state laws recognizing rape within marriage, being on guard for the ways our own political rhetoric might sometimes backfire isn’t a bad thing for feminists to do. It’s just plain smart.

While being sympathetic to these arguments, I’m not saying that all feminists should go have a Kumbaya circle and hold hands with the anti-feminists of Women Against Feminism—far from it.

There are plenty of Women Against Feminism posts that ought to piss us off, like the women who blame victims of sexual assault for their own abuse, engage in unmitigated slut-shaming, or reduce feminism down to an unrealistic “straw man” version of itself. Feminists have every right to object to those things and to fight back against them with all our political and personal might.

All photos via Women Against Feminism

What we don’t have the right to do, however, is pretend as if our own political agendas are so conceptually and practically airtight as to be beyond critique or question. It would do well for many of us to remember that there was once a time in our lives when we didn’t identify as feminists either. I know that I never would have become a feminist (and what a one I became!) if my own adolescent objections to feminism weren’t treated as valid enough for a serious, engaged response from feminists who took the time to disagree with me.

But, sometimes, we agreed, too. Recognizing that Women Against Feminism occasionally has something valid to say to feminists, that we still have a lot to learn, will make us all better feminists—and people—in the end.

Dr. Lisa C. Knisely is an assistant professor of liberal arts. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Gender and Women’s Studies, a master’s degree in Women’s Studies, and a doctorate in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. She is the editor of RENDER: Feminist Food and Culture Quarterly.

Photo via Kheel Center/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)