Terms of service agreements, and the privacy policies incorporated in them, are not just legal documents. They are the written manifestation of a company’s values, of a company’s ethical map. Outside of a mission statement, terms of service agreements and privacy policies provide us, the users, with some of the few written documents that can provide insight into a company’s culture.

From how the terms and policies are actually written, to the format they are presented in (both visually and in terms of actual notice to the user), to the actual tone of the agreement and policies, these are invaluable documents that actually let us see what duties, if any, the company thinks it has to the user aside from providing us a service and complying with relevant regulations and laws.

The thing is, most companies don’t write terms of service and privacy policies with this understanding.

More often than not, I’d venture to guess that “terms of service and privacy policies are the written documents that exude your company’s inherent value set” isn’t the starting point when companies are drafting these documents. Instead of that guiding principle, where each clause could be evaluated in terms of how it interacts with and impacts the user, more often than not the proximate goal of terms of service agreements and privacy policies is to create an impregnable legal shield against potential liability.

Enter Uber.

Uber has obviously been in a bit of hot water recently, to say the least. From potentially hiring opposition researchers to digging up dirt on its critics in the media—specifically spreading details about the personal life of a female journalist who has criticized the company—revelations about the party trick of Uber “God View,” and highlighting and tracking specific individuals to undisclosed third parties, almost all of the recent attention to Uber centers on the fundamental problem of terms of service agreements and privacy policies. If anything, Uber offers a perfect example of the market failure of user-friendly terms of service agreements and privacy policies.

Let’s take a look at some of Uber’s privacy policy.

Remember when I was describing what normatively should be the case when it comes to drafting terms of service agreements and privacy policies? The problem is, terms of service agreements and privacy policies are constantly and explicitly riddled with hedging clauses. For example: “except, but not limited to,” “including, but not limited to,” “including, but without limitation,” and “including without limitation.” This type of legal construction is somewhat understandable—it can be really, really difficult, and really, really tedious to enumerate every single bit of information that might, say, be collected by Uber when I use its mobile application.

But, when you understand terms of service agreements and privacy policies to be living documents that express a company’s deepest-held beliefs and values, clauses like “including but not limited to” and “including without limitation” at best do nothing to help inform the user about a company’s value set, and at worse, they willingly mislead a user in the most disingenuous of ways.

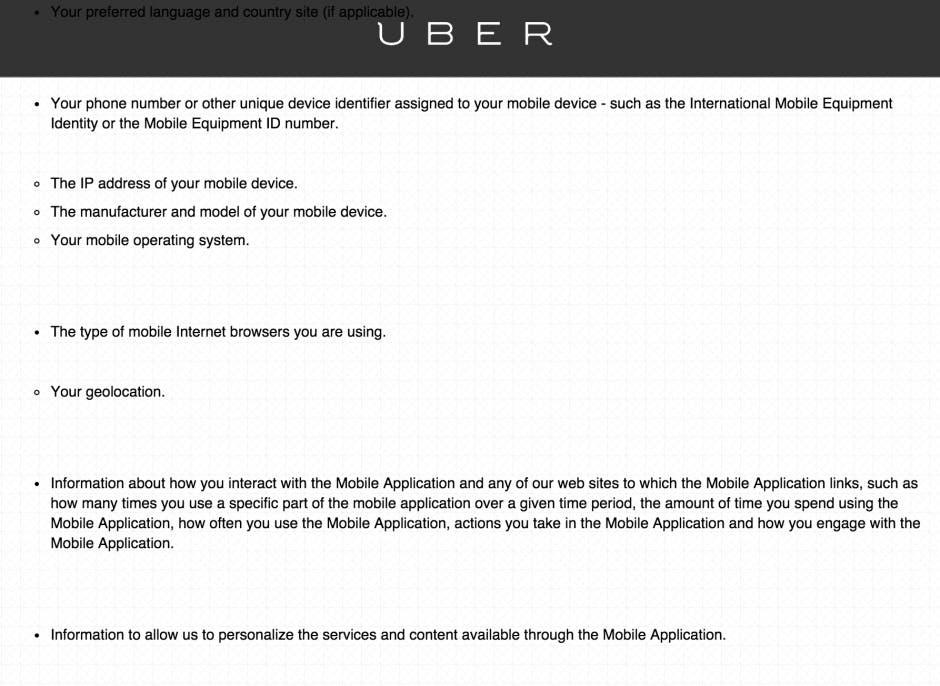

Uber, in eight bullet points, lists out information that its mobile application may automatically collect. Here’s what they say.

Except, this isn’t really the case. These are just a few, narrow, limited (pun not intended) examples.

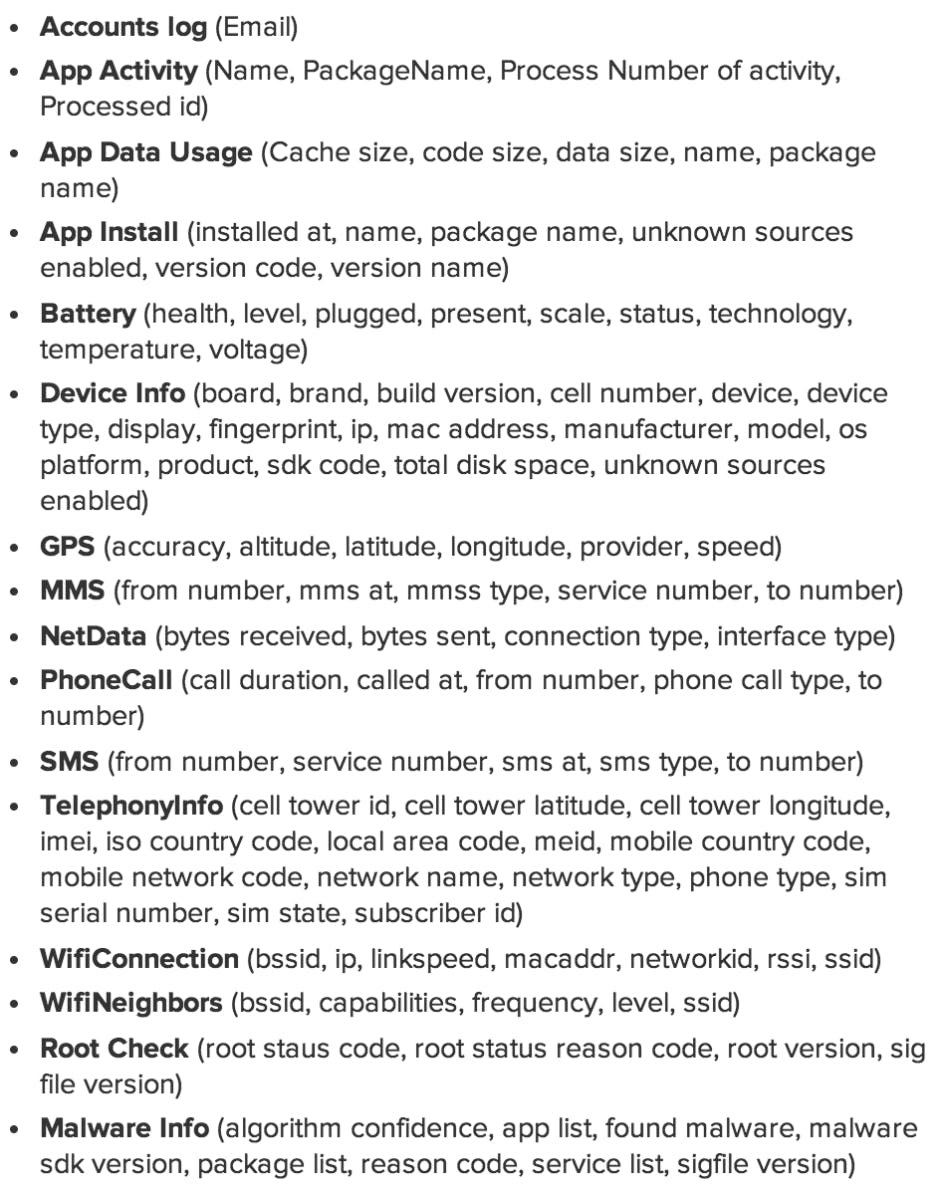

Instead of transparently disclosing the information that the application will collect automatically, the user is left in a cloud of dust, with little-to-no real knowledge of the information that Uber is actually collecting from its mobile application. In fact, thanks to some research by GironSec, we now know that Uber’s Android application is collecting a lot more information. Here’s a list of information that the Android app was found to be requesting and sending back to Uber:

Obviously, compared to what Uber disclosed they are gathering in their privacy policy, that’s a bit more information, all of which falls under, and is allowed by, the penumbra of “without limitation” clauses.

On November 18, the day after BuzzFeed’s report surfaced, Uber issued a blog post that attempted to spell out its privacy policy. In the post, the company tried to make clear that “Uber has a strict policy prohibiting all employees at every level from accessing a rider or driver’s data” and that “the only exception to this policy is for a limited set of legitimate business purposes.”

Unfortunately, but unsurprisingly, what those “limited set of legitimate business purposes” are is entirely unclear. While the post gives some examples like “supporting riders and drivers in order to solve problems brought to their attention by the Uber community,” they are construed just as that: examples, not an all-inclusive list of all the legitimate business purposes. Alternatively: including, but without limitation.

Two days later, Uber put out another post stating that the company had hired Harriet Pearson at Hogan Lovells to “conduct an in-depth review and assessment of our existing data privacy program and recommend any needed enhancements so that Uber can ensure that we are a leader in the area of privacy and data protection.”

There are a lot of possibilities for where Uber could go from here.

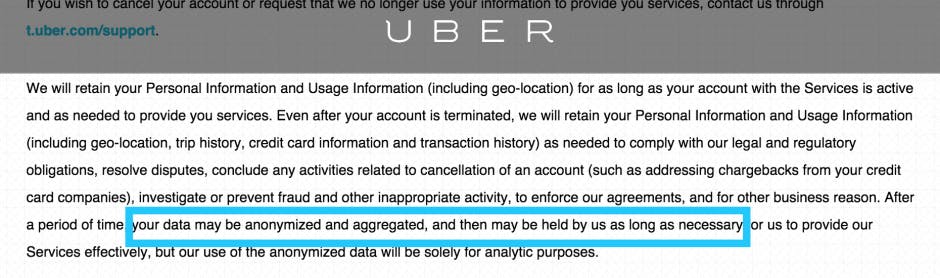

One possible idea is an internal audit reporting system, of sorts. In this hypothetical system, Uber, through a revised privacy policy, would be obligated to send its users an emailed report detailing instances X, Y, Z that their geolocation data was accessed by an Uber employee for legitimate business purpose A, B, C. Uber could also reform its data retention policies for active and terminated users. As of now, your data (even if you delete the application and terminate your use of the service) might be anonymized and aggregated after a certain period of time, but, it also might not! The policy gives you no guidance, no assurances. Sure, Uber certainly has some regulatory obligations to keep a user’s data for a certain period of time, but various statutes of limitation would govern how long Uber would actually need to monitor this data.

Retention of user data, even after you’re no longer a user.

On Medium, Bobbie Johnson argued that the reason so many of us hate Uber isn’t their bullying tactics, their “bro” culture, or their surge pricing, but that Uber forces us to confront the very qualities we don’t want to see in ourselves: “It shows us how, whatever objections [moralistic or idealistic] we might say we hold, we don’t actually care very much at all.”

What’s sad is that, despite some of the shock-and-awe coverage, these revelations about Uber and its privacy policies should not come as a surprise.

This is the expected outcome of a legal ecosystem in which terms of service agreements and privacy policies are explicitly, consciously designed to operate in way that creates the largest possible legal shield against any potential liability.

This is the expected outcome of a legal ecosystem in which, for too long, we haven’t actually cared much at all.

As revelations about how companies like Uber treat our data continue to stream out into the public, eventually there is a breaking point in which we collectively, finally realize that when it comes to terms of service agreements and privacy policies, there is a market failure. That’s the point at which companies begin competing on privacy—that’s when terms of service agreements and privacy policies really become those living, breathing documents that represent a company’s culture and represent an actual, interactive contract between the user and the service.

Simply put: Terms of service agreements and the privacy policies don’t have to be a zero-sum game. We just need to realize that, without limitation.

This post originally appeared at Nonsense in Context and has been reprinted with permission.