Streaming services, most notably Spotify, use what could be called a parimutuel royalty system: All the money collected goes into a big pool, Spotify takes their 30 percent off the top, and whatever is left is distributed to artists based on their share of overall plays. Spotify explains how it all works right here. It sounds perfectly fair and reasonable: If an artist wants to make more money, all they need to do is get more plays. But there’s a major disconnect in this economic model that has not been discussed widely: Spotify doesn’t make money from plays. They make money from subscriptions.

So how is that a problem?

Let’s say I am a huge fan of death metal. And nothing pumps me up more than listening to my favorite death metal band Butchers Of The Final Frontier. So I sign up for Spotify in order to listen to their track “Mung Party.” I listen to the track once, and then I decide Spotify isn’t for me. OK, so who got the benefit of the $10 I paid in subscription fees?

$3 goes to Spotify. Sure, that seems fair enough.

Roughly $0.007 will go to Butchers Of The Final Frontier. Hrmm, if only I had played the track one more time Butchers would have earned a penny.

But hey, wait a second. I paid $10. Where’d that other $7 go?

Spotify: “What $7?”

That other $7. Where’d it go?

Spotify: “We paid it out in royalties. For plays. Your boys got paid for their plays.”

Don’t be cute with me. Who got the $7?

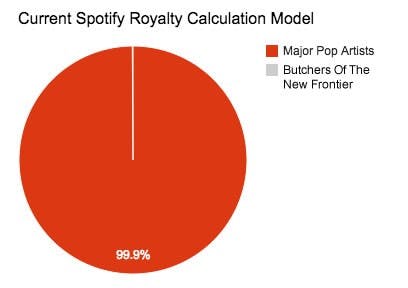

Spotify: “Look! A puppy!”

Since Spotify is so reticent on this topic, allow me to explain what will happen to 99.9 percent of the payable royalties generated by Butchers Of The Final Frontier: That money will largely wind up in the pockets of major pop artists like Calvin Harris, Meghan Trainor, Maroon 5, and Avicii. That’s right: Essentially all of the revenue that was solely generated by a small death metal band will be divvied up among a bunch of major dance-pop artists. The horror.

How could this be? It sounds inconceivably wrong, but under the current streaming royalty system, payouts are heavily tilted towards artists that get massive numbers of plays. And once a pop artist crosses a certain threshold it is a mathematical certainty that their royalties will actually exceed what their fans paid in subscription fees. Sadly this royalty bias towards popular artists comes at the expense of small independent artists. You could call this a case of the long tail wagging the dog.

Imagine if physical records or downloads were sold in this manner: Instead of an artist getting money directly from the sale of their CD or Mp3, it went into a giant pool, and the artist only got a percentage of the pool based on how often their music was actually played. It’s conceivable an artist could sell thousands of records generating hundreds of thousands of dollars of revenue, and still get a check for less than $10, with the majority of the money going to more popular artists.

In the past some have argued that forcing consumers to buy the whole album when they just want a single song is a “ripoff,” but I don’t think anyone believes the solution to this perceived problem is to have unrelated artists benefit from the sale of music they had no hand in creating. Yet that is exactly what streaming services are currently doing.

The irony is that each additional play actually costs Spotify money (servers/bandwidth/engineers aren’t free). So artists with fans who exhibit behavior that is less profitable for Spotify are actually getting a larger share of the revenue. That’s kind of fucked up, don’t you think?

OK, so what’s the solution?

Here’s what I think a fair(er) streaming royalty distribution might look like:

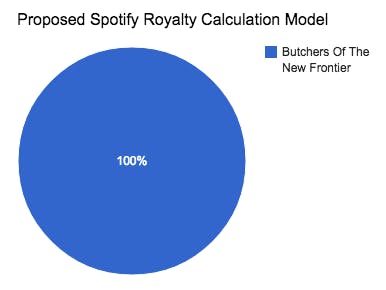

In a nutshell: Royalties should be paid based on subscriber share, not overall play share.

If I pay $10 and during that month I listen exclusively to Butchers Of The Final Frontier, then that band should get 100 percent of the royalties. I didn’t listen to anyone else, so no one else should get a share of the $7 that will be paid out as royalties from my subscription fee.

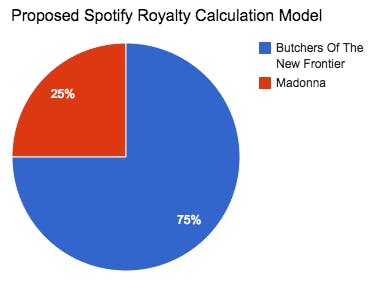

Now let’s say I listen to Butchers, but 25 percent of the time I’m listening to Madonna. My $7 of payable royalties would then be divided this way: Butchers gets $5.25 and Madonna gets $1.75. Again my subscription fee is divided up based on who I actually listened to:

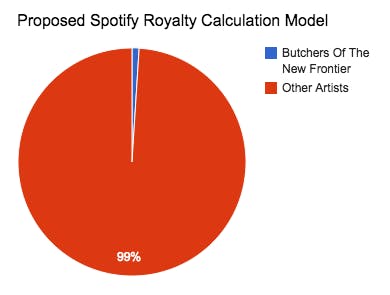

Now let’s say I just like to listen to death metal in the background while I work (my co-workers find this habit simply adorable). So I listen to Butchers once, but I also listen to 100 other artists once. In that case Butchers get 7 cents, and so does each of the other 100 artists:

And, accordingly, if Butchers was just one of 1,000 artists who each got played once, then Butchers, along with each of the other artists, would get $0.007 each. Which, ironically, is pretty close to what they stand to get under the current system.

In this far more equitable system the subscriber is paying to listen to certain artists, so those artists, and those artists alone, are the only ones splitting the royalties payable from that subscriber’s subscription fee. The economic model that drives Spotify is now connected to the economic model that drives artists: Get more listeners, not more plays.

What if a listener doesn’t listen to anyone at all? They forgot they had a subscription, or maybe they just weren’t in the mood to listen to music that month. In that case the money should be divided among all artists proportionate to their cumulative subscriber share, not their share of overall plays. In other words, let’s reward artists who actually bring in and sustain revenue, not artists who simply have listeners more likely to listen to the same tracks repeatedly.

Were Spotify to adopt this approach, some wonderful things would happen. Suddenly it would be possible for small artists with modest fanbases to generate meaningful royalties. If Butchers Of The New Frontier could convince just 5,000 people to listen to nothing but their music for one month, they would earn $35,000. Not a bad haul for one month!

Countless independent artists would suddenly have a stake in the system. Music genres that have dedicated but small fanbases (jazz, classical, and yes, death metal) would reap the benefits of their listener’s dedication. And perhaps most meaningfully, the fan would suddenly be empowered with the ability to directly support the specific artists and genres they actually enjoy, instead of seeing substantial portions of their subscription fees being used to prop up a culture of disposable singles.

This could also have a dramatic impact on the perception of the streaming music industry. What is the public hearing from artists right now? Many artists they love are passionate that streaming services represent a bad deal for artists. This has forced Spotify to increasingly take a defensive tone, with CEO Daniel Ek pleading for feedback from the industry on how to serve artists better.

This can change. If artists directly and visibly benefit from every subscriber they bring in, that could be very exciting and empowering, particularly for new artists. Every band on every corner would become a walking billboard for streaming services, and it’s easy to imagine a future where iPads would be present at every merch booth to sign even more listeners up.

But if indie artists do better, will that come at the expense of popular artists like Taylor Swift? I don’t think so. Real data is hard to come by, but I suspect artists like Taylor Swift would continue to do very well. Perhaps even better. Swift has popular full length albums, a large catalog, and very passionate fans. The most likely losers would be artists who do not have passionate fans, have only released a single or two, or who mainly get played in passive listening environments in combination with large numbers of other artists.

This could renew the faded glory of the full-length album: If an artist makes a track that finds its way onto numerous playlists, they will do all right, but not as well as an artist that can persuade people to listen to entire albums. In this model, the real benefit comes when you get people to listen to your music for sustained periods, as having lots of tracks played one after another is the most efficient way to get subscriber share.

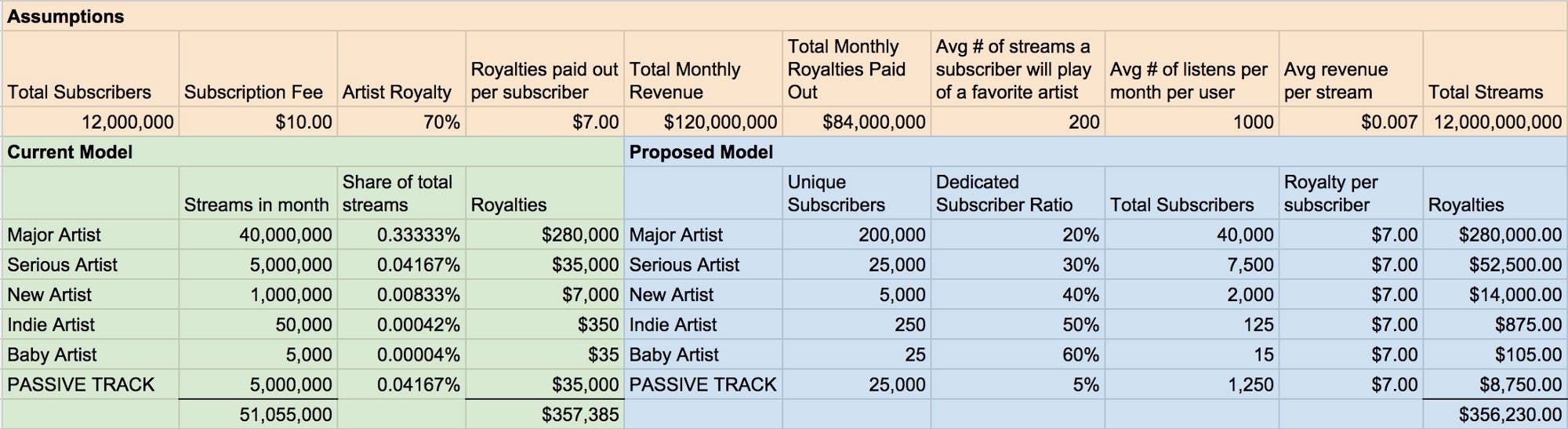

To get a sense of how this might work out, take a look at this breakdown:

The section to pay attention to is the blue section, where the ratio of dedicated subscribers to streams is labeled the “Dedicated Subscriber Ratio,” and the total number of dedicated subscribers is reflected in the “Total Subscribers” column. The idea here is that if one subscriber listens to an artist 70 percent of the time, and another subscriber listens to the same artist 30 percent of the time, that’s equivalent to one “Dedicated Subscriber” listening to the artist 100 percent of the time.

I’m not aware of any publicly available data on how many artists individual subscribers listen to when streaming, so for illustrative purposes I’m going to hypothetically suppose that as an artist increases in popularity, the proportion of casual listeners to uber-fans will increase as well.

The final category is “PASSIVE TRACK” which could be the pop single of the moment, or a song that has somehow found its way to numerous playlists for passive listening, but hasn’t done much to boost active plays of other tracks by the same artist.

As you can see, while the net royalty payout is essentially the same from Spotify’s perspective, nearly all categories of artists fare as well as they did before or better, with the sole exception being artists who either have no other tracks for listeners to play (a problem that can be remedied by releasing more quality tracks), or simply cannot command an active fanbase of their own. Meanwhile small indie artists see as much as a 300 percent boost to their revenue. These breakdowns are hypothetical, and this doesn’t remotely solve other artist concerns about streaming royalty rates, but it’s easy to see how this could be a step in the right direction.

So the elephant in the room is assuming that if you could even get the streaming services to sign on to this plan—and why wouldn’t they? It doesn’t cost them a cent, and everything about this is great for listener engagement—what will the major record labels think about all this? It’s fairly obvious that without the support of the labels this plan is dead on arrival. So, will they approve?

They should. This system would move revenue away from one-hit-wonders and towards artists that build and sustain lasting relationships with their fans. Given the expense, risk, and effort in making a hit song, this could work out wonderfully for the major labels over the long haul. As a side benefit it does an awful lot for small independent artists and labels in the meantime as well.

A fair(er) royalty system, a boost for independents, improving listener engagement, a renewal of value for the full length album: What’s not to love? In theory artists, labels, and streaming services should be able to unite around these common goals. But history has shown that getting the music industry to do the right thing, even when it’s in its own best interest, can be very challenging.

This post originally appeared on Medium and has been reprinted with permission.

Lena/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)