You can text your BFF a tiny cartoon of an eggplant, a lady flamenco dancer, two different cyclists, three different monkeys, a variety of books (in many different colors), every phase of the moon’s cycle, and an Easter Island head, but you can’t find a single black emoji. You can, however, send one emoji of two ladies in kimonos, a guy in a turban, and another avatar described as “vaguely Asian.”

If that doesn’t sound like a lot of diversity, it isn’t. These are the paltry offerings for non-white iPhone users, while the exact same emoji of a Caucasian woman gets represented nine times, between cutting her hair and doing her nails.

This has not escaped the notice of Apple customers, with even pop star Miley Cyrus pressuring the company to make emojis more reflective of the world’s population, in a tweet calling for an #EmojiDiversityUpdate. And after years of dragging their feet on the issue, Unicode, the team behind the creation of your favorite text hieroglyphs, promised that emoji diversity is coming in 2015.

How will the update work? The Daily Dot’s Michelle Jaworski explains: “Unicode’s plans include multiple skin color options based on the six tones of the Fitzpatrick scale, although the shades shown may change before the update is released,” Jaworski wrote. “On many phones, users will be able to choose their preferred skin color for a particular emoji by pressing and holding the emoji’s default version—which in this case appears to be yellow—and selecting from a miniature palette of options. It will be just like selecting an accented letter by long-pressing a vowel.”

Although long overdue, the push for emoji diversity is a crucial way to address the implicit racism of telling black users that they don’t need avatars that look like them—or telling Asians that they could have a lot more options for representation if they were a white lady in need of a manicure. Unicode’s emoji problems aren’t racism on the level of segregating schools, but sociologists have shown that these types of microaggressions can have long-lasting and profoundly harmful impacts on people of color.

Coined by Dr. Chester Pierce in the 1970s, the term microaggressions refers to “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color.” A Fordham University project on the subject collected photographs highlighting experiences of microaggressions from some of the students of color on campus, with many being asked questions like, “No, where are you from?” or “What are you?”

Whether its someone assuming you don’t speak English or touching your “ethnic” hair without permission, these experiences have a way of making people of color feel ostracized, made into an other, or just plain invisible. When not even your iPhone recognizes your place in the world, it’s easy to feel like you don’t exist.

And as Dr. Sue and David Rivera argued in Psychology Today, it’s the subtlety of these daily acts of racism that make microaggressions so powerful:

The invisibility of racial microaggressions may be more harmful to people of color than hate crimes or the overt and deliberate acts of white supremacists such as the Klan and Skinheads. Studies support the fact that people of color frequently experience microaggressions, that it is a continuing reality in their day-to-day interactions with friends, neighbors, co-workers, teachers, and employers in academic, social and public settings. They are often made to feel excluded, untrustworthy, second-class citizens, and abnormal. People of color often describe the terrible feeling of being watched suspiciously in stores, that any slip-up they make would negatively impact every person of color, that they felt pressured to represent the group in positive ways, and that they feel trapped in a stereotype. The burden of constant vigilance drains and saps psychological and spiritual energies of targets and contributes to chronic fatigue and a feeling of racial frustration and anger.

Although some might like to think we live in a post-racial society, microaggressions offer an implicit reminder of the real divisions that exist between us. “The simple fact is that racism—both personal, institutional, and structural—remains a force in American life,” wrote Jamelle Bouie in the Daily Beast. “It impacts the lives of everyone, whites included, and shapes the broad material circumstances of minorities in countless negative ways.” Bouie particularly points to racial inequality in housing, arrest rates, and the job market, where the fact of having a “black name” makes applicants less likely to get a callback for a position.

These inequalities pervade every facet of American life today, from how we engage in real life to the ways we connect with each other digitally. Although emojis have long been dinged for their diversity problems, they aren’t even Apple’s only race issue. Even though the company recently shot down a female masturbation app and one using the Obama “Hope” image, a number of notably racist applications have slipped into the App Store in recent years, including titles like Mariachi Hero Grande, I-Immigrate, Illegal Immigration: A Game, Ghetto Blaster, and Pocket God.

For reference, here’s a description of the latter, as provided by Latina.com’s Damarys Ocana Perez. “You play a God who crushes little brown people called Pygmies, who wear grass skirts and bones in their hair and have names like Ookga Chaka and Booga,” Perez said. “Send hurricanes their way, drown them, topple them like bowling pins with a boulder, set them on fire, drop bird sh*t on them.” What’s the lesson here? According to Perez, it’s the same one we learn from using emojis: “Brown people are expendable.”

Although the dawn of emoji diversity will be a way to begin addressing these problems, one must wonder why it took Apple and Unicode so long to get around to—or why they only took action when MTV reporter Joey Parker called out emoji racism in an email to Apple earlier this year. A justification for Unicode’s emoji whitewash is that the icons originated in Japan, where the black population is infinitesimal, but that doesn’t explain why there are two camel emojis, which aren’t indigenous to the island, either. Or why the company’s most recent update added gay and lesbian emojis, but still no black people.

It’s a similar conversation that the video game industry had when Ubisoft, the gaming studio behind Assassin’s Creed, claimed that creating a diversity of female characters would have “doubled the work” for the team; as Think Progress’ Lauren C. Williams argued, these examples further illustrate the ways in which the tech industry “consistently leaving out minorities when launching products.” Williams further concluded, “While emojis may seem like a relatively trivial issue, more diverse representation could make a huge difference.”

How would it do that? According to Georgetown University professor Sandra Calvert, the answer is simple: We all want to feel like we matter and we belong. “Everyone wants to see people like them,” Calvert said. “You learn about others and yourself by using these symbolic representations that we inhabit.” In a whitewashed world, what we too often learn is that only some of us count, while others are worth less than an eggplant. Diverse emoji won’t make the world less racist, but it will mean a lot to those who have to deal with that racism every single day.

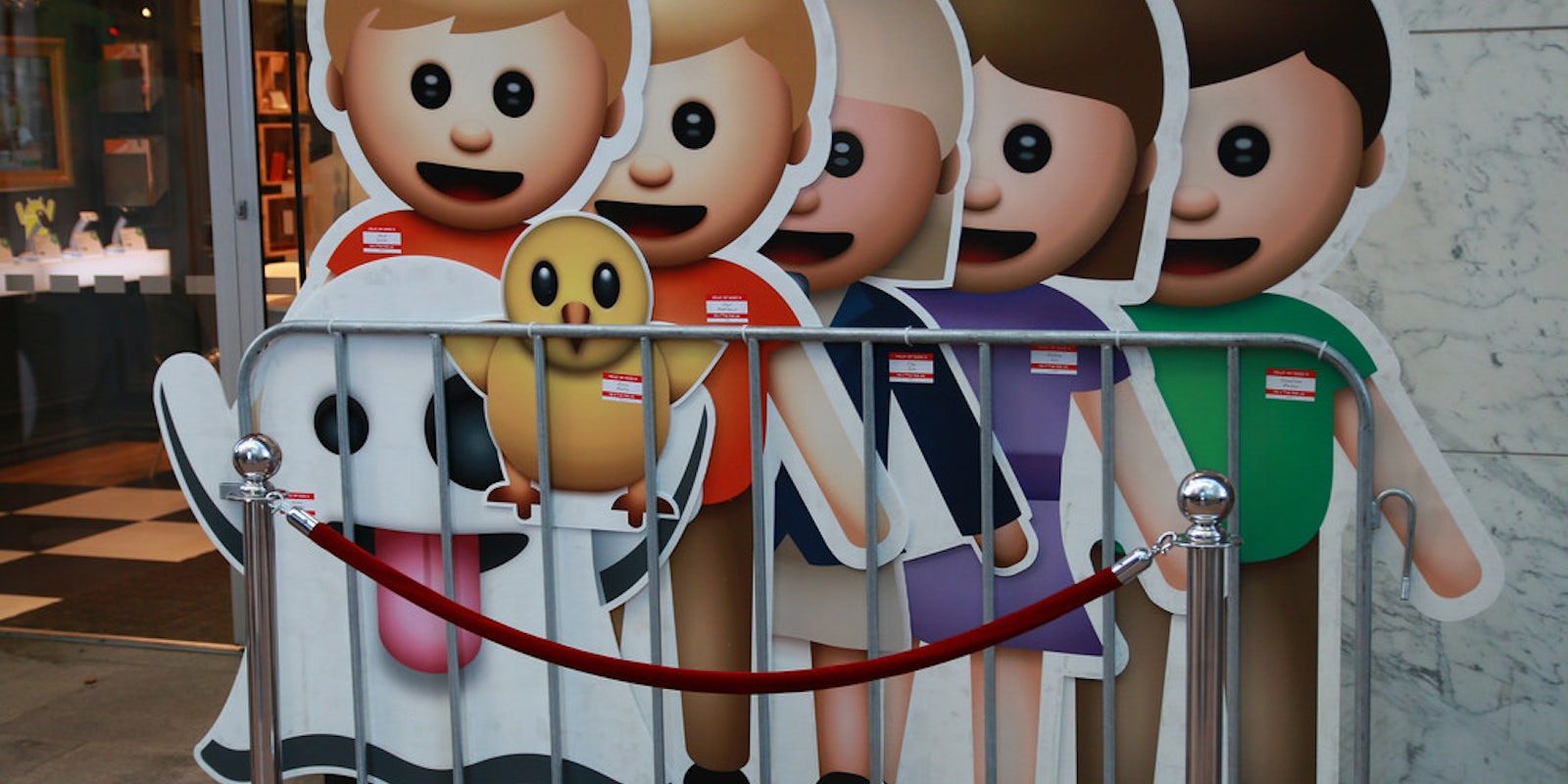

Photo by chrisjtse/Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)