For a movement largely founded upon a falsified report published by a disgraced doctor, the U.S. anti-vaccination movement is having its moment. After being declared all but dead back in 2000, measles is making a demanding return to the United States, most recently to visitors and staff of Disneyland in California. So far, 70 cases across six states have been linked to the amusement park, a depot for the perfect storm of a pandemic: international travel, crowded spaces, and children of all ages. After last year’s Ebola scare took the Internet by storm, it’s time to have a discussion about disease and accountability.

As even a few who have been inoculated are catching the dangerous illness, it’s worthwhile to pin some legal responsibility on the parents who, through reckless endangerment of their own children, have now created an entirely avoidable public health crisis. While anti-vaxxers might like to assume their decision is merely a personal one for their child, their ignorance is now a burden on the public at large, raising a host of challenging legal questions anti-vaxxers might not want answered.

The link between these outbreaks and the movement that believes vaccines are toxic, autism-causing poisons is clear. In a press release noting the sharp increase of measles outbreaks in the U.S., the Center for Disease Control reported 90 percent of all measles cases had either no vaccines or were uncertain of their history. “Among the U.S. residents who were not vaccinated,” the CDC went on, “85 percent were for religious, philosophical or personal reasons.”

A 2013 outbreak in Texas centered on a church with a pastor who believed prayer could replace vaccines.

What can make the issue worse is that anti-vaxxers tend to exist in population clusters, meaning where there’s one unvaccinated child, there’s likely to be more. A 2013 outbreak in Texas, for instance, centered on a church with a pastor who believed prayer could replace vaccines. Such groupthink encourages the chances of an outbreak significantly, exposing unvaccinated children to each other and therefore raising the number of patients who can expose it to the world at large.

Whether parents should face legal liability—maybe even prosecution—for their ignorance is, as you could imagine, a controversial topic. The idea first gained credence after a 2013 Journal of Law, Medicine, & Ethics paper argued quite deftly that, yes, if your child gets sick because of another parent’s neglect and dies, you could actually find that other parent legally responsible.

The first hurdle, notes the paper’s authors, would be to link causation of one child’s illness from another child’s unvaccinated status. While they note that 100 percent certainty would be impossible, “current scientific techniques could lead experts to state they believe that the preponderance of the evidence, with a 95 percent certainty or better” whether one child caught measles from another child. “Liability could certainly exist if a parent simply chose not to vaccinate his child and a death results.”

Measles is a highly infectious disease that can spread through a cough or a sneeze that, before vaccinations were common, killed over 500 people a year and gave 4,000 people encephalitis.

If that sounds extreme, listen to the doctors who say measles is an extremely serious public health concern. It’s a highly infectious disease that can spread through a cough or a sneeze that, before vaccinations were common, killed over 500 people a year and gave 4,000 people encephalitis. It’s exactly this level of contagiousness that has made vaccines so important in fighting measles.

“So what,” some anti-vaxxers might say. “If your child is safe, what do you care what I do with mine?” First, vaccinations are not 100 percent effective—just 99 percent effective. Of the 34 Disneyland cases who have been able to report their vaccination history, six were vaccinated and still caught the illness. Some populations can also not receive the vaccination, including infants under a year old and those allergic to some of the vaccinations ingredients. So by choosing not to vaccinate because your pastor or a forwarded email told you not to, you’re actually endangering those who cannot receive the vaccine whether they want it or not.

While the legal ramifications of this movement are still untested, courts tend to agree anti-vaxxers are exposing other children to undue risk. Last June, a Brooklyn district judge ruled against a set of parents who believed New York City public school’s mandatory vaccination policies were discriminatory, citing a 1905 case wherein a man refusing to get the smallpox vaccine was successfully fined. One plaintiff in the case even argued disease was of the devil: “But if you trust in the Lord, these things cannot come near you.”

One plaintiff in the case even argued disease was of the devil: “But if you trust in the Lord, these things cannot come near you.”

Aside from the public health risks, these outbreaks are also putting undue strain on an already under-funded disease response network. A National Institute of Health study found a 2008 measles outbreak in San Diego ran local and federal officials over $10,000 per case. While that’s money well spent to reduce the spread and effect of measles—the disease has a 0.3 percent fatality rate in the U.S. but a 28 percent fatality rate in less developed nations—these remain resources that could be better spent on less avoidable crises.

Posing a pertinent and real public health risk—as well as a preventable use of public resources—is far more than enough to have these parents assume legal liability. The causation is there: Going by the old “but for” test of liability, these outbreaks would not be occurring but for a small segment of the population refusing to vaccinate themselves or their children.

These parents have the right to refuse vaccination and should retain that right—let us avoid the idea of strapping down patients to give government-mandated injections. But let us also call the decision not to vaccinate your child what it is: neglect. It’s not just neglect of larger societal health concerns, but to the children themselves who have no say in the matter. And like a motorist that neglects to look before pulling out of the drive, anti-vaxxer parents should be prepared for the consequences of their actions—both real and judicial.

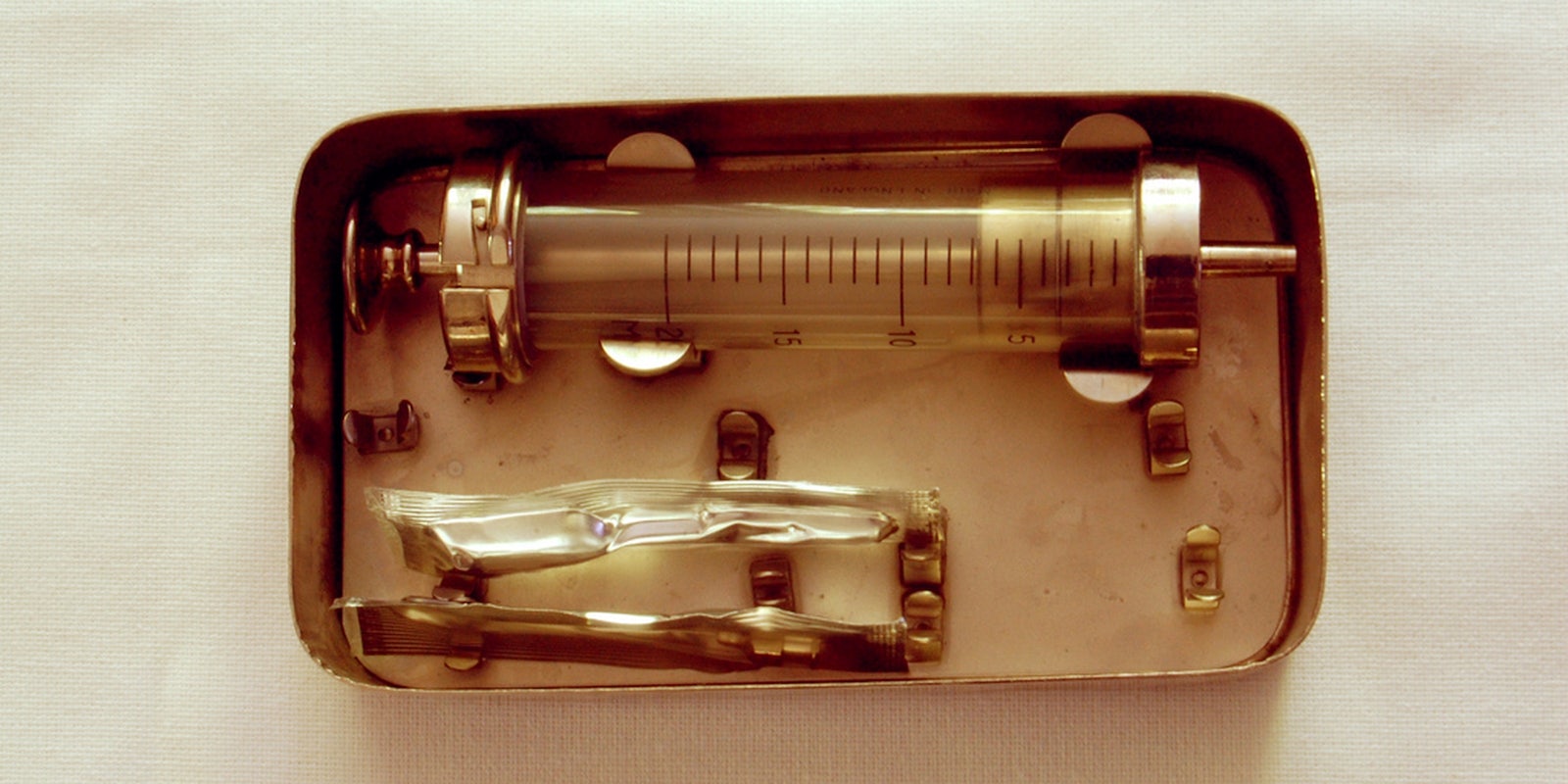

Photo via joelflintham/Flickr (CC BY-S.A. 2.0)