The latest Assassins Creed sequel has no playable characters that are women. You’d think it would be simple: just take the framework upon which you build your playable characters and modify it slightly to suit certain gendered characteristics for male and female options.

Sounds easy enough, right? But Ubisoft’s technical director James Therien protested yesterday that the latest installment of Assassin’s Creed had no women because it would have “doubled the work” of the animation team. For some perspective, it might be helpful to keep in mind that this is the same gorgeously animated, acclaimed franchise that devotes an entire subset of game play to tree-climbing.

Swinging from limb to limb high above the incredibly detailed world? High on the priority list of Assassin’s Creed features.

Putting a single woman into an active role in the game? Nah.

This isn’t even the first time this has happened recently. Earlier this year, the lead animator of Frozen protested that Disney‘s 3-D animation software literally didn’t possess the ability to make women’s faces look distinguishable from one another.

GIF via moopfloop

This is the same studio that employed a visual effects team of over 40 people in order to design the unique properties of snowflakes. Literally, the women of Tangled and Frozen were less distinguishable to Disney animation software than a pile of snow.

The tangle of issues and layers of sexism that contribute to this situation is overwhelming, but at the core is the fundamentally flawed way women are portrayed in comics, animation, and gaming: a feedback loop of sexual objectification and industry complacence.

When you perpetuate the idea, across various art-based mediums, that women in drawn art, comics, and animation must and should look and move with flowy, exaggerated gestures, graceful movements, and hips, chest, and ass thrust forward in order to pander to the male gaze at all times, then you make it easier, later on, to use your own sexist animation and art standards as an excuse for why you don’t have more women.

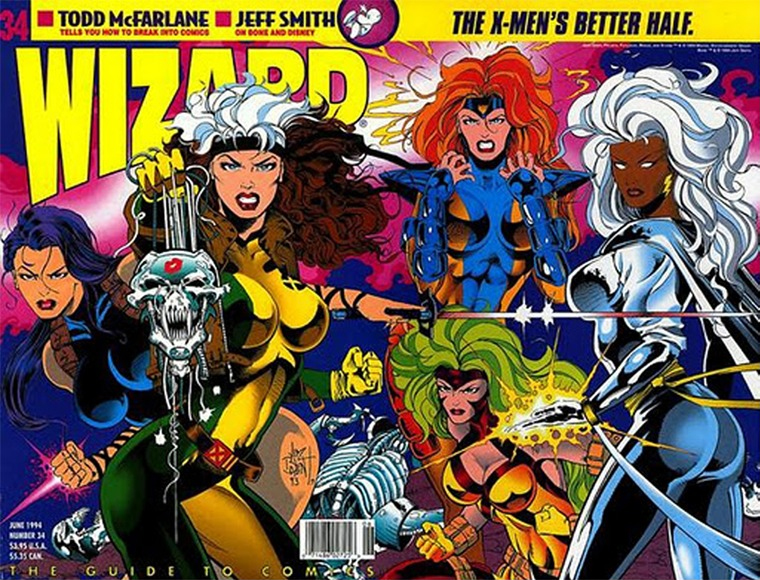

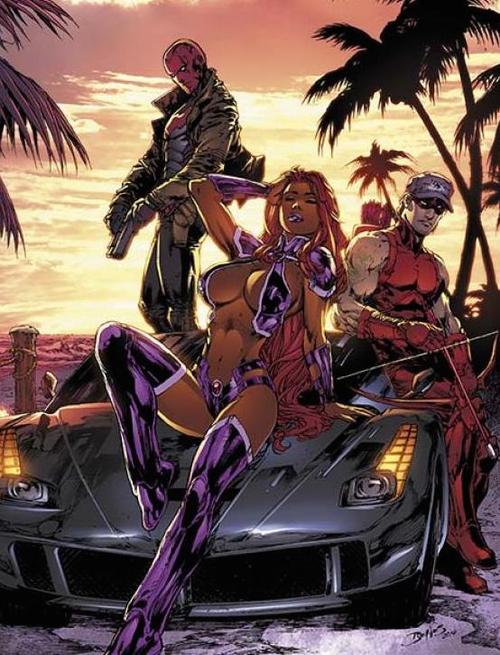

Take a look at these highlights from the annals of women in animation and illustration, in which characterization and individualization wars with and loses to the heteronormative male desire for as much T&A as possible.

Image via thehawkeyeinitiative

Image via hasdcdonesomethingstupidtoday

Gif via rainbowsandbutterfliesss

GIF via sabrina-von-dee

Gif via girl-with-the-eiffeltower-tattoo

Gif via bayonetta

Gifs via sadisticupid

Gif via iwantice

Gif via IGN

Gif via atrl.net

While the women in these examples all have vastly different characterizations, they all suffer from the same tendency of their animators to sexualize them. This isn’t a new phenomenon, either. From the earliest days of the Disney animation studio, its groundbreaking all-male team of animators codified the stylistic traits of female Disney characters: big eyes, baby-doll cuteness, and plenty of sultry gestures and curves:

Gif via artgeekpop

However little practical relationship these kinds of portrayals have to real women, they have endured. In 1986, in order to communicate the “twist” ending that the lead character of Metroid had been female all along, Nintendo memorably removed her full-body armor to reveal a woman in a bikini for no apparent reason. Even in 8-bit format, Samus Aran was hilariously sexualized.

Screengrab via YouTube

The history of gaming is full of similar moments. And the more female characters are sexualized on-screen, the less they have in common with their male counterparts. Of course animators will be reluctant to build interchangeable male and female characters—it means they would have to design women who walk, run, and idle normally.

You know, the way their male playable characters do.

Industries that rely on animation appear to be okay with this double standard. But being okay with the kind of animation that prioritizes objectifying details like women’s hip thrusts and hair details over their facial characteristics leads to hilarious and hurtful unrealistic expectations for women.

Nowhere is this more evident than in gameplay. Take this Dragon Age video, a literal example of the Hawkeye Initiative in animated action. In this genderbend, the playable male character of Hawke has been given the game mechanics of his female counterpart—exaggerated hip movements, demure, passive feet-shuffling, and a hilarious sexy idling position, complete with outthrust leg and Angelina Jolie pose:

These exaggerated moves look ridiculous on both versions of these characters, but we’re conditioned to accept them as part of the way animated female characters are portrayed. And our reactions when the same absurdly sexualized gestures are applied to both genders couldn’t be more different, or more sexist:

Gif via DAPS

Gif via ONTD

So if these poses are so absurd, why are women so routinely drawn and animated in ways that utilize them? The answer is that women in animation are drawn primarily by men.

Men dominate the fields of animation both within the entertainment industry and the gaming industry. In 2010, only 17 percent of all animators in the Hollywood-geared Animation Guld were female. In gaming, the stats are even worse: as of last year, only 16 percent of artists and animators in the gaming industry were women. In comics, as of March, women barely comprised 16 percent of Marvel’s roster of cover, pencil, and ink artists. DC was even worse: barely 11 percent.

#womenaretoohardtoanimate? Thats ok #Ubisoft, women are hard to animate when you’ve never seen one. #MaskingMisogyny

— Cole M. Sprouse (@colesprouse) June 11, 2014

When women are allowed to move and act naturally in games, the way that they have in many of the most acclaimed games with female playable characters, the results are empowering and interesting, as we see in this set from Mass Effect 3‘s Commander Shepard:

Gifs via mahariela

We can see this evolution in the game mechanics of Lara Croft, which have gradually become less exaggerated and stylized over time. Although these two mirror scenes take place in very different contexts, we can clearly see the change in the visual approach to the character.

Gif via tombraidergifs

Gif via troybaker

In the mechanics for the newly announced Rise of the Tomb Raider, Lara Croft’s movements are desexualized and full of active movement:

Gif via negativeoneten

Gif via pride-rock

The movements of Femshep and the modern Lara Croft aren’t overtly gendered. By allowing the range of female identity to be equal to those of male characters, the animation of those characters is more standardized as well. Game designer Jonathan Cooper, a lead developer on earlier Assassin’s Creed and Mass Effect installments, pointed out this feature in an interview with Polygon yesterday.

“We made sure that their skeleton was identical so it could be shared across everything,” Cooper said, speaking of his work on Mass Effect‘s playable characters. “I think maybe the female had shorter arms or something. We might have also replaced some animations like holding a gun or stuff, but otherwise they’re just shared across all the characters, all the different races.”

On Twitter, Cooper had earlier called bullshit on Ubisoft’s claim that animating a playable female character would have taken “double the work.” While one developer working on the game estimated that it would need up to 8,000 replacement animations to insert a playable female character, Cooper suggested that it would really only have taken days. “Man, if I had a dollar for every time someone at Ubisoft tried to bullsh** me on animation tech.”

If Cooper is correct, then the problem with Assassin’s Creed and Frozen is not that women are too hard to animate; it’s that the industries which rely on animation also rely on outdated and sexist standards for how women should be visually portrayed. To update those technologies with a less complacent eye for how animated female characters are drawn might mean less eye candy for the male animators who create them.

It’s not that women with overtly sexualized features can’t also be empowering. Women have long derived empowerment and self-confidence from characters who pander to the male gaze, like Ryuko from Kill La Kill or Juliet from the uber-violent Lollipop Chainsaw.

Gif by jeremypamyupamyu

But when women are consistently portrayed this way, across a spectrum of media designed for audiences of all genders and ages, it makes it harder for real women to be taken seriously as anything more than sexual objects by the industries that work to erase and sexualize them. No wonder the average salaries of female artists in the gaming industry are a whopping 29 percent less than their male counterparts.

Portraying animated women without overtly sexualized elements doesn’t mean that women need to lose all traces of beauty or feminity. Take Lightning Farron from Final Fantasy 13. She’s never objectified. She’s also able to be badass as welll as sensitive, loyal, nurturing, and protective.

Gif via kennytrevas

Gifs via champion-of-etro

Ultimately, if the fundamental technological principles behind the animation used to create entertainment products don’t make it easy for those products to have an inherently equitable gender ratio, then those fundamentals are flawed. But that also means that the industries which rely on animation have more opportunities than ever to reinvent visual standards for female characters.

It starts by acknowledging the need to do better by female characters, female artists, and female audiences. While a full solution encompasses change at every level of the industries that utilize sexist visual standards, it’s easy to see where to start. Move away from the visual emphasis on objectified body parts and start illustrating women the way they want to be viewed in real life:

As people.

Illustration via pitoxlon/deviantART