Update: Following publication, widespread reports emerged that eBravo shut down; the app is no longer available on the Google Play Store. There are also reports that the Daily Dot’s website is blocked for customers of PTCL and StormFiber. The Daily Dot has contacted eBravo, PTCL, Cybernet, and StormFiber for comment.

Napster became a household name practically overnight when it launched in 1999. Unfortunately for music lovers—and fortunately for artists—the person-to-person music sharing site’s rise was as meteoric as its fall. A little more than two years after the first Napster user shared hits like Britney Spears’ “Hit Me Baby One More Time” with a friend, a lawsuit filed by major recording artists forced the company to close. In Napster’s wake, people as young as 12 were penalized huge sums of money and, in a few cases involving adults, arrested.

The saga remains one of the most infamous intellectual property scandals of all time.

The unauthorized reproduction and distribution of intellectual property has long been big business and an even bigger source of disputes. Intellectual property (IP) rights have caused conflict between entire countries and even been used as a weapon of war.

The internet launched an era of IP theft that’s bigger, faster, and more pervasive than ever.

When most people think of online piracy, as digital IP theft is commonly known, their thoughts naturally turn to the dark web, shady criminal organizations, or perhaps sharing their Amazon Prime password with a friend desperate to see Fallout—some of the most common forms of such theft. Digital piracy by seemingly legitimate companies is a lesser-known way that IP can allegedly be stolen from its rightful owners. Sources say that this form of piracy is particularly rampant in Pakistan, the world’s fifth-most populous country.

There, they say, online piracy of film, television, video games, and software isn’t the exception, it’s the rule. Research shows that companies there distribute content from around the world, seemingly without license to do so. Materials reviewed by the Daily Dot show that the content includes the latest releases and titles that appear to be banned in the country. It’s all available by simply paying for services like an American would subscribe to Xfinity or Hulu.

Sources say this amounts to a massive theft of intellectual property that’s being conducted out in the open, including being facilitated by major telecommunications companies with international ties. People inside Pakistan believe the government has little inclination to crack down on the practice, however. Records reviewed by the Daily Dot show that the Pakistani government itself owns a majority stake in a company that distributes Bollywood content, a particularly remarkable fact given that Pakistan has banned showing Bollywood in theaters for years (Bollywood is available on streaming services like Netflix and Amazon Prime Video). Given how pervasive the issue is, some wonder why the United States government hasn’t intervened to protect American companies’ intellectual property.

U.S. Intellectual Property Counselor for South Asia John Cabeca declined to comment on the specifics of the matter but acknowledged that the government is aware of it.

“…[I]nformation digital piracy in Pakistan is very much on my radar and a subject of much discussion in my interactions with the Pakistani government,” Cabeca told the Daily Dot via email.

This story is based on government records, interviews with multiple sources familiar with international digital piracy, online records, and two sources inside Pakistan, one of whom provided screenshots and video evidence pre-recorded and in real time.

The Daily Dot is using pseudonyms for its sources in Pakistan to protect their safety. “I like my arms and legs attached to my body,” said Nour in a remarkably casual tone given the matter at hand. The other source, Dara, said that those who speak out have been known to be incarcerated and tortured. Amnesty International reports that in Pakistan in 2022, “Grave human rights violations continued, including enforced disappearances, torture, crackdowns on peaceful protests, attacks against journalists and violence against religious minorities and other marginalized groups.”

Systemic piracy

Dune: Part Two has been heralded as one of the best movies of the year, attracting audiences to theaters worldwide at a scale that some say hasn’t been seen since the pandemic. The epic sci-fi film grossed half a billion dollars worldwide within weeks of opening, according to Variety.

Dune: Part Two became available on Amazon Prime Video on April 16. It costs $25 to rent or $30 to buy a digital copy.

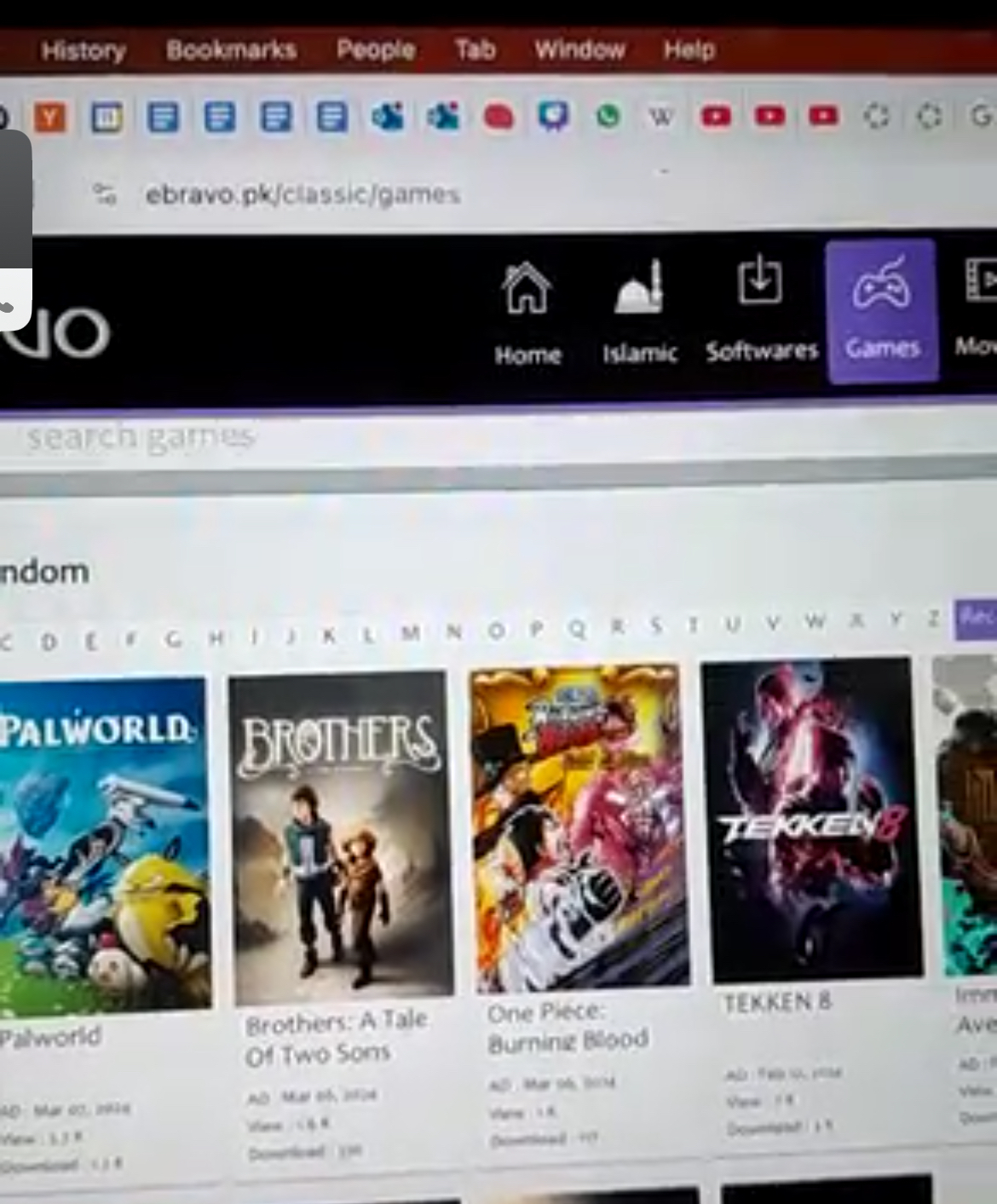

With the right subscription, Pakistanis could already have watched it without paying any extra fees. On April 15, Nour provided a video to the Daily Dot in which they were able to simply stream the film. A week prior, they sent a video that showed the film was available to watch on that service, eBravo. Nour also did an hourlong video chat during which they showed both the hardware and content available from multiple companies, including eBravo, that exclusively serve the Pakistani market. The web addresses of all the sites displayed in Nour’s recorded videos, video chat, and screenshots include .pk, the country code for Pakistan.

eBravo did not respond to request for comment sent via the contact form on its website. Its website claims that “unless otherwise stated,” it or its licensors own the intellectual property rights for all content distributed on the app.

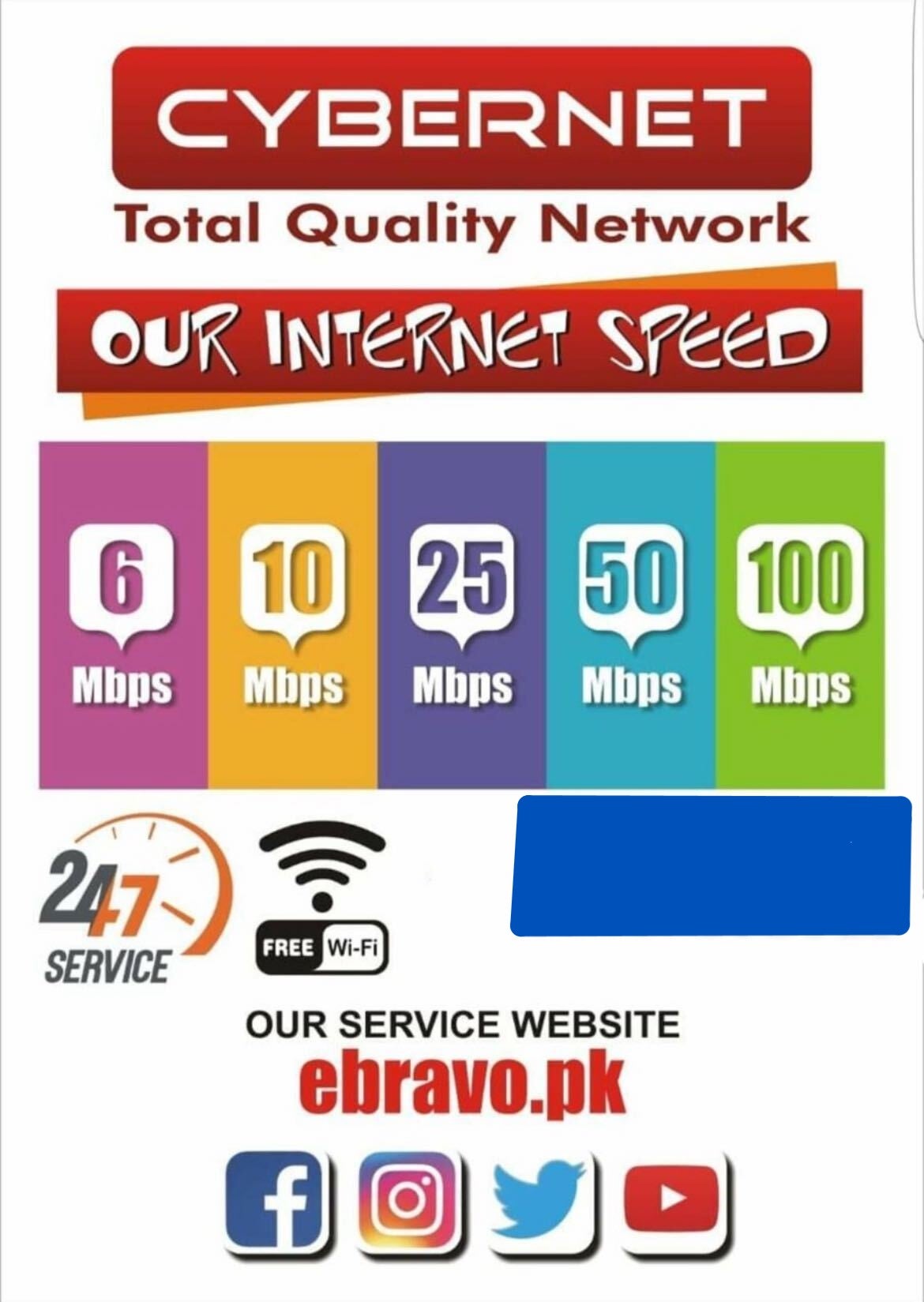

Records show that eBravo’s hosting company is Cyber Internet Services, aka Cybernet. Cybernet is a subsidiary of the Lakson Group, a conglomerate owned by one of the richest men in Pakistan.

eBravo has a close business relationship with Cybernet. The company denies that it owns eBravo, insisting it merely provides web services.

“We can confirm that neither Cyber Internet Services (Pvt.) Ltd nor Lakson Group have any ownership of ebravo.pk which is a customer for domain registration/hosting,” a company representative said via email.

Nour provided the Daily Dot with a screenshot of a promotion in which Cybernet described eBravo as “our service website.”

Nour said that Cybernet owns eBravo, which the company denies, insisting theirs is merely a business relationship. Online commenters have said for years that access to eBravo is limited to Cybernet subscribers, which could simply be indicative of a contractual relationship. In 2020, one described eBravo as Cybernet’s “sharing entertainment portal” on a message board dedicated to gaming. In 2017, another user on the same message board wrote that you “must” subscribe to Cybernet to access eBravo. In 2022, a redditor claimed that it is possible to access eBravo by subscribing to either Cybernet or StormFiber, which is also a subsidiary of the Lakson Group.

Cybernet said that the onus is on eBravo to ensure it is complying with IP rights and that it promptly investigates and takes “appropriate action” in response to complaints or orders from regulatory agencies, courts, or in the form of Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) takedown requests about its customers like eBravo.

In a follow-up email, Cybernet said that after receiving the Daily Dot’s inquiry, it notified eBravo that it had 24 hours to stop distributing any content it does not have a license to. It also said that if eBravo doesn’t comply, it will investigate and potentially disable its service.

The company took issue with being asked about its business relationship with eBravo, including whether both are owned by the Lakson Group.

“We cannot help but feel an element of predetermination or bias in the manner in which you are investigating. We would therefore urge you to look at this matter objectively and share the information you have because your emails to us clearly show that you do not fully understand the nature of our services and that the accusations that you have mentioned in your emails are belied by the truth,” a representative from Cybernet wrote.

The Lakson Group did not respond to a request for comment sent via the contact us form on its website.

The Lakson Group’s businesses range from fast food to consumer goods to the media. It has business relationships with some of the best-known American brands in the world, including Colgate-Palmolive, McDonald’s, and the New York Times. Colgate-Palmolive Pakistan is a subsidiary, and a different Lakson Group subsidiary is the exclusive McDonald’s franchisee in Pakistan. Neither Colgate-Palmolive nor McDonald’s responded to requests for comment.

Reporting from 2012 stated that the Lakson Group’s flagship publication “is partnered with the International Herald Tribune which is the international edition of the New York Times.”

The New York Times, which is currently suing Microsoft and OpenAI alleged copyright violations, did not respond to a request for comment.

Records and materials provided to the Daily Dot show that many Pakistani companies distribute foreign content they may not have the rights to. On its website, Lakson Group subsidiary StormFiber boasts that it offers over 200 channels. The Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA) reports that it has only issued 140 channel licenses. Amid a nationwide crackdown on cable operators illegally distributing Indian channels, a local news affiliate noted last year, “Only PEMRA licensee channels can distribute on cable TV networks.”

In October, Reuters reported that PEMRA banned television stations from giving airtime to 11 people, including “journalists considered close to former Prime Minister Imran Khan, individuals accused of criticizing the military or the government, and others that have been ‘proclaimed offenders’ or absconders by courts.” In 2022, per Reuters, it suspended a television station’s license after it broadcast one of Khan’s speeches. The editor of a weekly newspaper told the outlet that PEMRA at times engages in “brazen censorship” or functions as “a means of controlling the channels, which are often fined, questioned or slapped with notices for their programming.”

PEMRA is described as an independent regulator, but critics question how independent it is given such actions.

Both Dara and Nour said Pakistan’s telecommunications industry is overwhelmingly indifferent to IP rights.

Dara described a system in which powerful telecom companies blatantly ignore IP rights, either intentionally or through willful indifference. Dara worked in the telecommunications industry until the late teens. Although he has switched careers, he believes that little has changed. He recalled having a meeting with the CEO of a large internet service provider (ISP) in which the subject of pirated content came up.

“He asked us this question: ‘Why pay for content?’” Dara said, adding, “There was a time they were the only player in this, and the CEO is telling me why pay for content. Why not just steal it.”

He likened it to killing people for money simply because it’s profitable.

“You’re killing businesses, and actually livelihood by stealing content. And your justification is because you can make money from them pretty much justifies anything that you want,” Dara said.

As they left the meeting, he realized that it would be impossible to operate legitimately in the industry because you’d be competing with companies that keep costs low by pirating content.

Andy Chatterley is the founder and CEO of MUSO, a company that tracks digital piracy and provides copyright protection to a wide variety of creators, including major television, film, gaming, and live sports brands. Chatterley was not familiar with reports of widespread piracy in Pakistan but told the Daily Dot that it is possible that studios and television stations have confidential deals with the Pakistani companies that distribute their content.

“Unless you’ve got access to contracts, unless you [were in] those conversations, it’s very difficult to know,” Chatterley said from his recording studio in England earlier this month, noting, “They may not want to speak to the journalist.”

A possible reason a company like Warner Bros., which did not respond to an inquiry, might not want to discuss whether it has granted distribution rights to Pakistani companies is because the Muslim country’s government is extremely restrictive about what it allows to be shown there. However, it is arguably unlikely that Warner Bros. granted any company the distribution rights to Dune: Part Two before it was available to rent in American households.

Chatterley agrees. “[It] certainly sounds like it shouldn’t be happening, but we just don’t know what they might be negotiating. And there could be all kinds of stuff going on behind the scenes.”

Irrespective of whether there are secret deals in place, it is inarguable that intellectual property theft bleeds money from the American economy. In 2017, the Associated Press reported it costs the U.S. $600 billion annually, roughly the equivalent of the gross domestic product (GDP) of Belgium.

Digital piracy has exploded since then. MUSO found that from 2021 to 2022 alone, film piracy increased nearly 40% and visits to websites that pirate television increased nearly 10%. Chatterley said that wouldn’t include data about unauthorized distribution of content by seemingly legitimate companies. He also pointed out that Americans are actually the biggest consumers of pirated content, per MOSU’s data.

“It’s a huge problem. And it’s not getting any better,” he said.

The government’s role in piracy

Digital piracy is an international phenomenon that is not specific to Pakistan. In fact, after years on the U.S.’s list of trading partners on the priority watch list, meaning they were viewed as least protective of IP rights, Pakistan was downgraded to the watch list in 2016. The IP includes goods and content that’s patented, trademarked, and copyrighted.

The U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) reported that the Asian nation was downgraded to the watch list “due to the Government of Pakistan’s significant efforts to implement key provisions of the Intellectual Property Organization of Pakistan (IPO-Pakistan) Act of 2012 and the newfound determination with which Pakistan has approached IPR over the past 12 months.”

Today it remains on the watch list alongside Brazil, Egypt, Germany, Japan, Kenya, Kuwait, Nigeria, South Africa, and Turkey.

As the USTR suggested in 2016, if Pakistani companies do steal foreign content, it should technically be possible to get legal redress. Like most countries, Pakistan is a signatory to the WIPO Copyright Treaty, which requires it to provide a legal form of recourse for aggrieved parties. Whether there is a realistic means of seeking relief is another matter, however.

Pakistan’s WIPO office did not respond to a detailed inquiry about the process for enforcing intellectual property rights and its record of the same.

Sekou Campbell, a partner at Culhane Meadows, has practiced international intellectual property law for 15 years. Campbell explained that under the terms of WIPO, a copyright held in one country must be recognized by all other nations that have ratified the treaty. Enforcing those rights can be expensive and complex, though, particularly in countries where the legal system is unreliable.

“It may be an issue with the rule of law in Pakistan,” Campbell said without commenting on the specifics of allegations of digital piracy there. “…Even if you get a valid order, is it enforceable?”

Campbell further opined that countries “that are more heavy on the censorship side don’t tend to have very good copyright enforcement.” Pakistan is notorious for censoring the population and stymying freedom of the press.

Dara affirmed that suing isn’t a viable option. Cases drag on for years, often at great expense, and a positive outcome is unlikely, he said. “That’s why most people would not go to court,” he said.

He also said that, while Pakistan’s 235 million citizens arguably make for a large customer base, its economy is such that the actual value of those customers is significantly lower per person than in other more developed countries, which further disincentivizes companies from filing suit.

Everyone the Daily Dot interviewed for this article agreed that the end user is the least to blame. Unlike an American whose Love is Blind binge was cut short because Netflix cracked down on password sharing, the average consumer there may not realize they’re watching pirated content—after all, they simply subscribe to a service and watch what’s available.

Suppression of the press further helps mask the issue because people only know what they’re told, Dara said. He believes that, in addition to being stifled by the government, the press is kept quiet by telecom companies who can give or take away their audience at any given moment by taking their channel off the air or putting it in a prime spot on the directory.

“Cable operators are so powerful they can manipulate media,” he said.

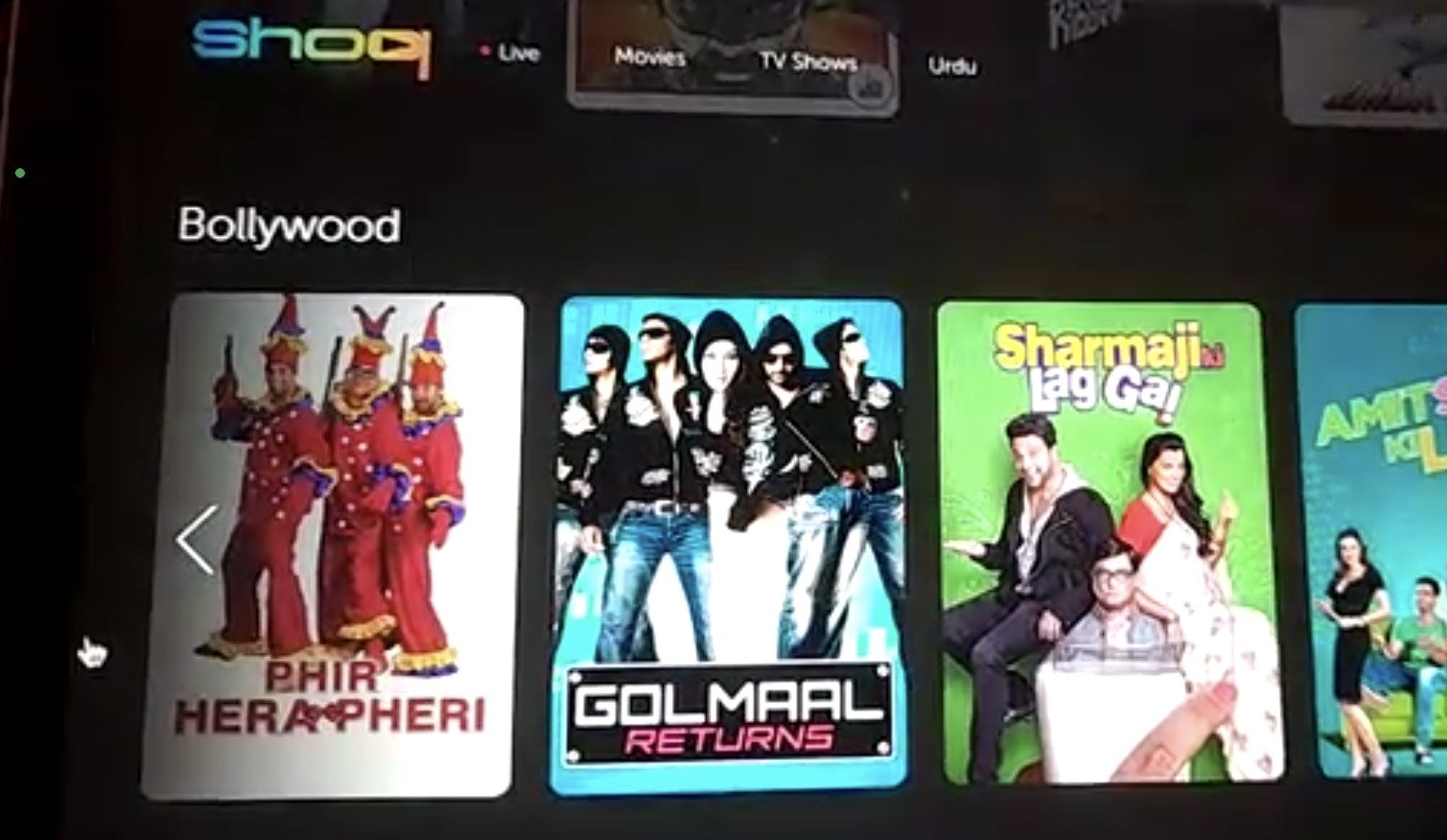

There is some indication that Pakistan is less inclined to enforce intellectual property rights, as Campbell alluded to. The government is a majority owner of Pakistan Telecommunication Company Ltd, more commonly known as PTCL, which provides television, internet, and telephone. The Daily Dot reviewed materials both in recording and via livestream showing that PTCL distributes Bollywood films and television, including through its app, SHOQcast. It is possible that it has a confidential agreement to do so, but that would arguably be an odd arrangement given that the country has banned Bollywood content from being shown in theaters or distributed by cable companies.

(PEMRA is technically an independent regulator, but has been criticized for doing the government’s bidding.)

Nour said that this is a clear example of how the government says one thing and does another. They pointed out that the country blocked access to X in late February, yet during that time both the government itself and President Asif Ali Zardari continued posting on the platform on their official accounts.

According to Dara, it’s an open secret that the military is behind blocking websites like X, Facebook, Wikipedia, and others, for a range of reasons including immoral content, pornography, or in reaction to protests against alleged election rigging. That any branch of the government can block such sites arguably shows that the country could, but chooses not to, step up enforcement of IP rights.

No one speaks out, he said, because of the severity of the risk.

“When it comes to opposing opinions to the military there’s something dangerous, right? And I wouldn’t say like if I was being quoted [by name], I wouldn’t say it. I have a family. I have kids. Definitely not,” Dara said.

Given how pervasive piracy is—a 2010 article claimed that 84% of the software used there was pirated—it seems unlikely that major corporations aren’t aware of it. Yet at least some major American companies seem nevertheless willing to do business with Pakistani companies that may be pirating content.

At the Mobile World Congress in February, PTCL and Google announced that they were partnering to offer a SHOQ branded television box powered by Android. The box features multiple Google apps, including the Play Store.

“This means Google looked at this app and thought it was OK,” Nour opined.

Google declined to comment. PTCL did not respond to requests for comment.

Nour believes that outside pressure is the only way to clean up digital piracy in Pakistan. He suggested that foreign companies who do business with those who engage in systematic IP theft could be helpful in this regard.

“Disney Plus would be furious if they saw this,” Nour said of the company’s content being distributed there. PEMRA’s list of authorized stations does not include Disney. Disney did not respond to an inquiry.

Some companies have recently reportedly sought to enforce their copyrights in Pakistan. The Daily Dot reviewed a copy of a letter from one to PEMRA demanding it stop several Pakistani companies from distributing its content without a license. StormFiber was one of the companies.

PEMRA did not respond to inquiries.

Nour believes that widespread piracy of international intellectual property is holding Pakistan back. They opined that, while some may turn a blind eye in the pursuit of profits, other companies are less likely to form legitimate business relationships there because they know their property rights will not be protected.

“We continue to engage on these and other issues in support of a stronger, more effective ecosystem in the country,” said Cabeca, the U.S. intellectual property rights counselor for South Asia.

Send Hi-Res story tips and suggestions here.

The internet is chaotic—but we’ll break it down for you in one daily email. Sign up for the Daily Dot’s web_crawlr newsletter here to get the best (and worst) of the internet straight into your inbox.