Last weekend, Grantland writer Molly Lambert tweeted an Iggy Azalea pun about Amelia Bedelia, the protagonist of the eponymous children’s book series about a “literal-minded housekeeper” who misunderstands her employer’s orders. Jay Caspian Kang, an editor at NewYorker.com, then tweeted a screengrab of the Wikipedia entry for Amelia Bedelia, with a chunk of text highlighted:

@mollylambert @rachsyme wait what is this. pic.twitter.com/LxHf3gYZZ5

— jay caspian kang (@jaycaspiankang) July 27, 2014

I saw the tweet last Sunday, while I was scrolling through my timeline right after I got out of the shower. When I saw Kang’s tweet, I immediately screamed “WHAT” and sat on the bed in a towel for a good hour, furiously tweeting and texting my friends until my boyfriend came in and yelled at me to put some clothes on, goddammit, we have somewhere to be in 20 minutes.

I wrote that Amelia Bedelia edit in 2009, with my best friend Evan during our sophomore year of college. As he recalled when I called him later that evening, “we were stoned out of our minds” and had just come from the McDonald’s drive-thru to get chicken selects when we decided to edit Wikipedia pages for various semi-obscure children’s book authors. (I think we also did one for R.L. Stine, but Evan says no.)

It was total bullshit: We knew nothing about Amelia Bedelia or the author of the series, Peggy Parish, let alone that she’d been a maid in Cameroon or collected many hats. It was the kind of ridiculous, vaguely humorous prank stoned college students pull, without any expectation that anyone would ever take it seriously. “I feel like we sort of did it with the intention of seeing how fast it would take to get it taken down” by Wikipedia’s legion of editors, Evan says.

But apparently, it hadn’t been taken down at all. There it was, five and a half years later, being tweeted as fact by relatively well-known members of the New York City media establishment. And a quick search of “Amelia Bedelia Cameroon” proved that Kang and Wikipedia weren’t the only ones taken in by the joke:

The “Amelia Bedelia was a maid in Cameroon” factoid had been cited in a lesson plan by a Taiwanese English professor. It was cited in a book about Jews and Jesus. It was cited in innumerable blog posts and book reports, as well as a piece by blogger Hanny Hernandez, who speculated that Amelia Bedelia’s tendency toward malapropisms was inspired by Parish’s experiences in Cameroon, as “several messages can be misinterpreted between a Cameroonian maid who is serving an American family.” One blogger even speculated that Amelia Bedelia wasn’t a maid, but a slave.

It was cited in the Amelia Bedelia entry on the website TV Tropes and Idioms, and Peggy Parish’s Find-A-Grave page. It was even cited by Mr. Amelia Bedelia himself: Herman Parish, Peggy’s nephew and author of the books after his aunt passed away in 1988, who apparently told a reporter from the Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier that his aunt based “the lead character on a French colonial maid in Cameroon.”

I was stunned. How did a joke we made up about Amelia Bedelia while we were stoned get repeated all over the Internet for more than five years, by blogs and reporters and elementary school students and even the author of Amelia Bedelia himself? Did Evan and I inadvertently start a giant Wikipedia hoax about an obscure children’s book author?

To find out why the edit hadn’t been taken down, especially considering there was a typo in it, with “North” instead of “North Africa,” I spoke with Milowent, a Wikipedia editor who’s considered an expert on Internet hoaxes. He was the first to find the “Amelia Bedelia Cameroon” Google results. He basically said that the efficacy of a Wikipedia hoax—regardless of whether it was intended as a hoax, as mine wasn’t—depends on “how believable it looks.”

“There’s no systematic review system,” he told me via Twitter. “The creator of S’Mores’ name [a reference to a Wikipedia editing scandal about where the name of S’mores came from] was edited multiple times over the years—even made it into a cookbook…I am not sure anyone knows how many hoaxes like this lurk on Wikipedia.”

But given the tone of the writing—”her vast collection of hats, notorious for their extensive plumage” is about as snarky as snarky can get—and the fact that Evan and I didn’t even cite a source, why would no one see any red flags? How could the Amelia Bedelia Cameroon myth go unedited or unquestioned for so long—if not by Amelia Bedelia’s readers, by Parish himself, who is still alive and well and writing books for the Amelia Bedelia series? (His latest, Amelia Bedelia Goes Wild, was released last March.)

Milowent doesn’t know, but he has some ideas. “I guess Parish (the current author) is not an internet guy, and has no friends on the internet,” he speculated. “And surely readers [of the series] are too young to question anything. It’s incredibly ironic that so many people have literally accepted that fabrication, like Amelia would herself.” (I reached out to Parish to offer a mea culpa of sorts, and also to get comment, and have not yet heard back from him.)

Milowent also says that had Evan and I played a little faster and looser with the details—if we had said Amelia Bedelia was based on a prostitute in French colonial Cameroon, rather than a maid, for instance—the edit would have likely been spotted and debunked.”‘Subtle’ vandalism like this sticks around the longest,” he said. “Say the Hardy Boys are gay, it’s out right away. Cameroon, not so much.”

I’d be lying if I said that the words Milowent uses to describe what Evan and I did—”vandalism,” “fabrication,” “hoax,” “lie”—don’t stick in my craw a little bit. As a journalist, and as someone who has always self-identified as deeply honest to a fault, it makes me more than a little bit ashamed to think that a falsehood I made up on the Internet had so much weight.

It also doesn’t make me feel great that this particular lie had duped so many people that it’s been propagated dozens and dozens of times by allegedly credible sources. I wondered if it had made its way to the Parish family, and if so, how they feel about it. (I imagine more than a little bit bemused, not to mention perplexed as to why a couple of stoned teenagers would want to spend their time writing false factoids for an Amelia Bedelia Wikipedia entry.)

When I spoke to my co-author Evan on the phone the other night, he admitted he shared my guilt. “I guess I do kind of feel bad now that I know it’s been up for so long, and so many people repeated it,” he said. “We were just doing it because it was funny. And it was. It was really fucking funny.”

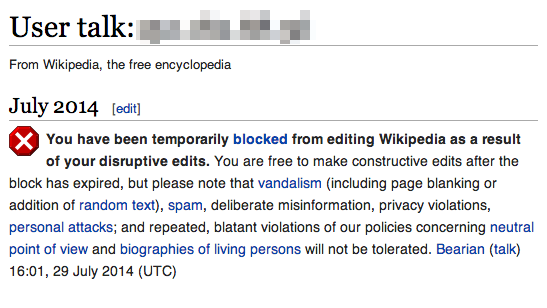

My inadvertent Wikipedia hoax was not the first of its kind: There have been hundreds like it, many of which have done far more damage than mine did, or ever will. (Milowent has promised to revert the edits to the Amelia Bedelia entry. He also pointed out another one for Peggy Parish herself that I forgot about, which apparently included the [false] book title Amelia Bedelia Knits A Cat A Christmas Sweater in the bibliography; that one has since been deleted.) Nor is it particularly surprising in itself that Wikipedia is not a bastion of accuracy, or that its army of editors would fail to notice a subtle inaccuracy in an entry for a fairly obscure American children’s book author.

Ultimately, what I learned from my inadvertent Wikipedia hoax was not that Wikipedia itself isn’t reliable, but that so many people believe it is. My lie—because that’s what it was, really—was repeated by dozens of sources, from bloggers to academics to journalists. They knew better than to attribute Wikipedia directly, because even a seventh-grader knows citing Wikipedia as a source is tantamount to admitting that you haven’t done any research at all. Instead, they referred to the source of the Amelia Bedelia Cameroon lie in vague terms, such as “the literature I’ve read” on the subject, or even to Parish himself.

In the end, I don’t feel as bad about my Amelia Bedelia Wikipedia lie, and what it might say about my integrity both as a journalist and as a person, as I do about what it says about the future of information in the digital age. Joseph Goebbels once said that if you tell a lie enough times, it makes it true. I always thought that was the bullshit self-justification of a sociopath and professional prevaricator, but now that I’ve seen the process of a lie becoming fact firsthand, I think there’s some credence to it.

I told a lie on the Internet about Amelia Bedelia. It was dishonest. It was amoral. I tricked a lot of people. But even now, five and a half years later, I still have to agree with Evan up to a point. It was (kind of) funny.

Update:

Illustration via Harper Collins | Remix by Jason Reed