Ever wondered what the equivalent to an online relationship was in the Victorian era? Romance by telegraph, of course.

And while it’s a popular myth that the age of the Internet has brought with it a host of new concerns about identity and unseen connections, a 123-year-old American novel currently available in the Gutenberg Library proves that the more the wireless changes, the more our obsession with long-distance romance stays the same.

Wired Love is an 1880 novel written by Ella Cheever Thayer when she was 31. Thayer based her novel on her own experience as a telegraph operator in a Boston hotel; Wired Love promptly became a bestseller, and stayed that way for the next decade. And with good reason: as described by Collision Detection, it’s a novel full of arch witticisms about long-distance affection and the high probability of the person you meet via telegram being subpar in person. It’s also swimming with questions that still linger in our collective conscious today: How can we trust someone before we’ve met them? Under what circumstances are first impressions the right ones? And is it possible to love someone without having met them first? (We’ll pause while you cue up Savage Garden.)

The epigraph of Wired Love reads, “The old, old story,”—in a new, new way,” your first hint that the story in its pages is a timeless one. It opens with a scene straight out of a modern-day IM conversation. Nattie, our heroine, is initially impressed with the speed of the unknown telegraph operator on the other end of the wire:

“Dear me!” she thought, rather nervously, “the country is certainly ahead of the city this time! I wonder if this smart operator is a lady or gentleman!”

This quickly leads to her obsessing over the meaning of the words he (or she) is typing, trying in vain to discern their tone without knowing anything about the person on the other end.

For a small one, “Oh!” is a very expressive word. But whether this particular one signified impatience, or, as Nattie sensitively feared, contempt for her abilities, she could not tell. But certain it was that “X n” sent along the letters now, in such a slow, funereal procession that she was driven half frantic with nervousness in the attempt to piece them together into words.

The public has long been fascinated with the idea of the unknown correspondent, of deceptive first impressions alternately created or conquered by long-distance correspondence. Whether it’s Cyrano de Bergerac writing letters in disguise to the beloved Roxane, or Jimmy Stewart courting his co-worker sight unseen in The Shop Around the Corner, we’ve always had a yen for romances formed from direct glimpses into the mind of the person you love, long before you’ve gotten a face to match.

The age of the Internet has largely warped this longing for connection into equal parts anxiety and urban legend. Tales of true love found online through sites like eHarmony and Match.com have largely been overshadowed by horror stories: Craiglist killers and tales of the mythical “catfish,” a term coming from the title of a 2010 pseudo-shockumentary. Catfish purports to be a straightforward documentary about a regular guy who discovers that the hot artist he thought he was sort-of dating is actually a stereotypical middle-aged housewife, starved for love and possibly suffering from Munchausen’s by Internet.

Yet Catfish‘s storyline seems carefully crafted, far too easily packaged to be anything but a contemptuous satire of Internet hysteria. The truth about most online relationships is a truth much more universal—which is why it’s so nice to be reminded that a century ago, our stories of wireless correspondence were playing out exactly the way they do today.

It helps that both Nattie and her mysterious Mr. “C” are whip-smart, lively characters. But there’s also every mistaken-identity trope to be found here, exactly in the way you’d expect them to play out in a contemporary novel of online romance. By the end, when good sense and optimism prevail over all the potential scariness of the unknown stranger, it’s as though Thayer herself is reaching through the annals of time to rap the makers of Catfish on the knuckles.

In honor of Thayer, Nattie, and her thoroughly modern relationship with “C,” we present our favorite stories of love formed, and in some cases disguised, through the written word.

The Five Best Stories of Epistolary Romance

The Browning Letters. Apart from being a tremendous story of lifelong passion ignited wholly from afar, the dizzyingly romantic correspondence between poets Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning that led to a shocking elopement has one other recommendation—it’s all true. And as of last year, it’s all online.

Cyrano de Bergerac. The oldest and still the classic of all romance-in-disguise narratives, it stays just as fresh on film in the hands of Steve Martin wooing his Roxanne.

The Most Happy Fella. Frank Loesser’s gorgeous, misunderstood operetta is a poignant early tale of “Catfishing,” with the search for true love facing off against class issues, age differences, culture shock, and betrayed trust.

The Shop Around the Corner. In addition to being the quintessential “unseen romance” story, Shop Around the Corner has also proved to be the longest-lasting. In addition to being, itself, an adaptation of a 1937 Hungarian Play, the 1940 film classic has been remade into other familiar favorites: the Judy Garland musical In the Good Old Summertime, the stage musical She Loves Me, and Nora Ephron’s final Hanks/Ryan outing, You’ve Got Mail.

Griffin and Sabine. This 1991 bestseller is one-part mystery, one-part romance, one-part myth, as an unhappy postcard-maker, Griffin, embarks on a gorgeous correspondence featuring pop-out drawings, actual postcards, and beautifully crafted letters from the elusive Sabine.

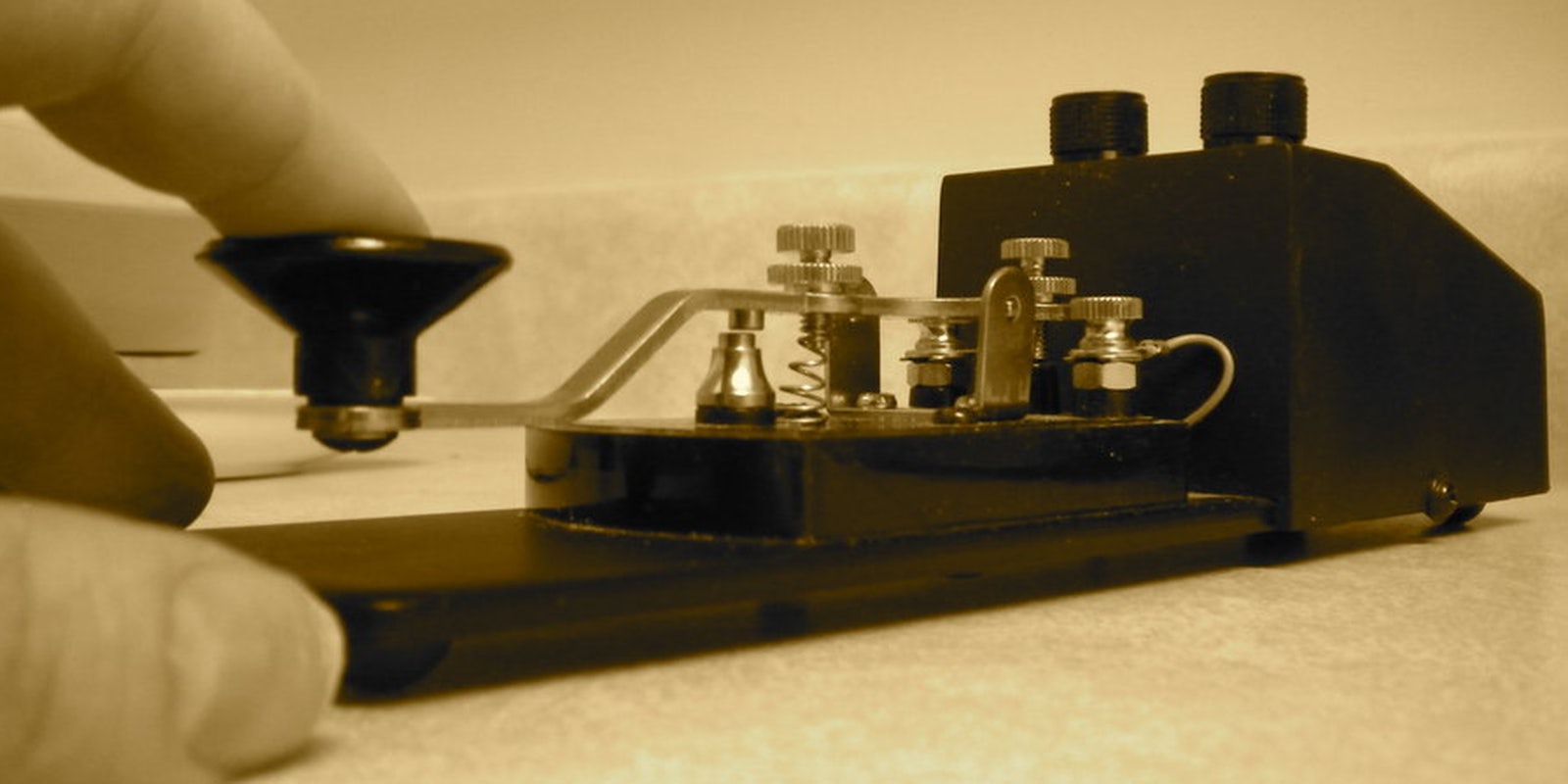

Photo by kodemaster/deviantART