The world’s oldest profession has changed very little over the millennia. But following the rapid expansion of the Internet, the sex trade is suddenly finding new ways to thrive in cyberspace, even as it appears to be vanishing from the streets, according to a comprehensive new study commissioned by the U.S. Department of Justice.

By compiling hundreds of firsthand accounts from pimps, prostitutes, and police, the report depicts the modern commercial sex economy and for the first time shows how strikingly different its 21st century industry appears.

The new 380-page report from the Urban Institute profiles the industry in eight U.S. cities, chosen based on their number of convictions, existing human-trafficking task forces, and the opinions of sex trade experts, among other factors. These include Atlanta, Dallas, Denver, Kansas City, Mo., Miami, Seattle, San Diego, and Washington, D.C.

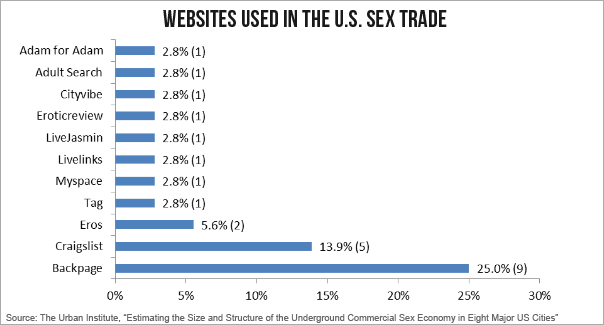

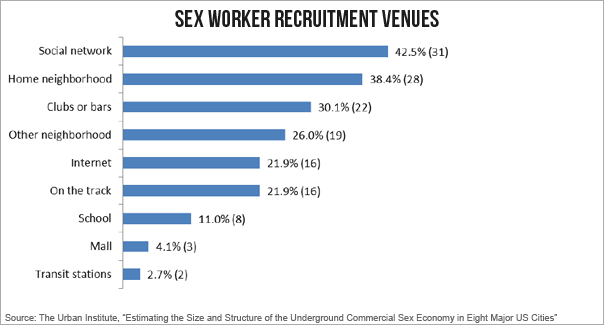

Websites such as Craigslist and Backpage, not to mention social media, are now the preferred channels for pimps to connect with clientele, stake out potential recruits, and research business opportunities elsewhere.

The shift from street-walking to competing with online ads is, at least in part, attributed to the perceived benefits of conducting business over the Internet, as opposed to problematic and sometimes dangerous, face-to-face negotiations. Pimps interviewed overwhelmingly considered in-calls, scheduled with clients via the Internet, to be the most secure way to finalizing a transaction.

Pimps are forced to constantly change their practices as they become aware of new tactics used by agents of the law trying to apprehend them. In San Diego, for instance, a decline in sex workers willing to perform out-calls was attributed to the routine arrests of women showing up to an undercover agent’s hotel room.

The perception that Internet prostitution is safer is also a contributing factor to some pimps abandoning the streets.

“Over the years, the Internet became an easier way to get money without having to take so many chances as far as injury or assholes on the outside,” a jailed pimp told researchers.

“You never know what happens at night—a lot of creeps come out.”

The online sex trade has also provided some women with greater opportunity to sell sex, without relying on pimps, in a way that makes them feel safer and more anonymous.

“The Internet allows them to do it by themselves,” a Seattle police officer reported.

“The smartphones allow them to access the Internet. They allow them to not only take pictures of themselves, store the pictures, and then post the pictures and do the ads right from their telephone. They don’t even need to have a computer anymore.”

But there are still plenty of pimps on the Internet. For one, it allows them to reach new and wealthier clientele. Others may use it to evade law enforcement by staying on the move, travelling city to city, and booking appointments in advance.

Pimp-controlled women and underage girls are often advertised online as independent escorts, which, for law enforcement, makes identifying their pimps especially difficult.

In almost every city, law enforcement reported that the majority of underage sex workers now offer services online, whereas several years ago, they were primarily on the street. However, most minors cannot function online independently. As one Dallas police officer noted: “[Children] can’t book hotel rooms, they can’t get cards, they can’t get the credit cards to put the Internet ads out. They have to have an adult to do all of that.”

Quotas are often imposed on pimp-controlled women and girls, ranging from $500 to $1,000 per day. The prices for sex acts ranged from $60 for oral sex and up to $200 for intercourse.

Sex workers who remain on the street have been impacted by prostitution’s online popularity as well, with less customers available and a decline in the value of their services. In the late 1990s, street workers reportedly made between $5 to $150 for oral sex and $5 to $250 for intercourse, compared to the 1970s and 1980s when oral sex went for $50 to $100 and intercourse for $60 to $300.

Another way the Internet has influenced the sex trade is in the way “dates” are sold. Instead of charging per sexual act, which is how business is traditionally transacted on the street, online sex workers frequently arrange prices based on the duration of the appointment.

“A 15-minute date typically costs about $60, a 30-minute date ranges from $60 and $150, a 60-minute date ranges from $120 to $250, and a ‘full service’ date (during which any number of sex acts may be performed for a predetermined fee) costing as much as $300 to $350, if not more. ‘Full service’ dates are reportedly common with online work.”

For a variety of reasons, online sex workers make significantly higher profits than those on the street. Experts attribute this to the ability of sex workers to advertise their prices upfront, with the prerequisite that johns pay for a minimum amount of time. Online sex workers are also less likely to suffer the effects of drug abuse, meaning they’re less likely to trade sex solely for drugs.

In almost every city, sex workers operating on the streets demonstrated habitual drug use, and typically sold sex to feed their addiction. For the last several decades, the price for a sex act has been matched with the cost of a rock of crack cocaine: a mere $20.

“Most of the Internet-based girls, I mean they’ll use drugs too, but not to the extent that the street girls will use them,” a Kansas City official said.

“Street girls are basically doing a trick to get a rock, they get high, when that high comes down, they’ll do another trick to get another rock and it’s basically just a vicious cycle. The other girls plan ahead a little bit more.”

One respondent, whose location was not reported, blamed a significant drop in prices online on drugs: “It’s because young girls are snorting powder, which is cheaper today, so they can charge less money.”

Conducting business online might be extremely profitable for sex workers, but it does come with its own drawbacks. An Atlanta woman said she was guaranteed to make $250 an hour, but characterized the work as exhausting. “They call the shots for the hour. They can cum as many times as they want to.”

Another disadvantage to posting ads for sex using sites like Backpage is that it’s just as easy for police to monitor. While the majority of prostitution charges in, for instance, Kansas City, stem from arrests on the streets, officials admit it’s much easier to conduct surveillance operations online.

“There’s chat rooms not just for the working girls but for the guys that visit the girls, the johns will go talk about the girls, that’s a pretty good resource for us,” an official with Kansas City law enforcement said. “I’m sure the guys that go there know that we frequent that also. But it’s a big help for us—trying to locate where girls work or trying to figure out what activities they perform.“

In September 2012, Craigslist halted its adult advertising services after a public letter, signed by 17 attorneys general, was written to CEO Jim Buckmaster. “No amount of money, however, can justify the scourge of illegal prostitution, and the suffering of the women and children who will continue to be victimized, in the market and trafficking provided by Craigslist,” the letter read.

But this decision was actually a disservice to law enforcement, according to one federal agent: “They are a legitimate business but they just have this illegitimate side. So they were cooperating with us in many ways and when they went away it is kind of like the hydra, when we took one away five more popped up.”

An official interviewed in San Diego repeated the agent’s concerns, condemning more recent attempts to shut down Backpage, stating that sex traffickers will simply “go further underground.”

A chief finding in Urban Institute’s report was that only a small fraction of sex traffickers in the United States are actually investigated or prosecuted under the law. The lack of attention paid to these crimes, which are often tantamount to human slavery, results from a lack of resources and political support. The misconceptions of the public, with regards to the prevalence and severity of sex trafficking, also plays a factor.

At present, there’s no way to precisely measure the size of the U.S. sex trafficking industry. This is largely because of inconsistencies in how sex trafficking data is accumulated. As reported by Urban Institute, prior survey results and economic modeling studies produced median estimates of the minimum number of U.S. victims anywhere from 3,817 to 22,320. Less than half of 700 sources on sex trafficking reviewed contained empirical research and only 12 percent of the research was peer-reviewed.

According to a report on human trafficking, published at Cornell University in 2005, the global profit generated through forced commercial exploitation in the sex trade was roughly estimated at $33 billion per year. Other trafficking experts, such Siddharth Kara, have placed the amount above $50 billion.

The report’s conclusion? Pimps, sex traffickers, prostitutes, child pornographers, law enforcement agents, and even experts all agree: The Internet is good for the sex trade, regardless of whether you’re trying to stop it, or profit from it.

As the report declares: “An increasing online presence makes it both easier for law enforcement to track activity in the underground sex economy and for an offender to promote and provide access to the trade.”

Photograph via Massimo Catarinella (CC BY-SA 3.0)