Siara Hughes has always had a bit of trouble relating to others. She’s sensitive to light and heat—to the point where sitting on a recently vacated chair is very uncomfortable and upsetting to her. She always struggled to maintain eye contact, which got her in trouble with her teachers at school. She knew she was a little different from other people, but it wasn’t until she had a label for her unique experience, Asperger’s syndrome, that she began to feel understood.

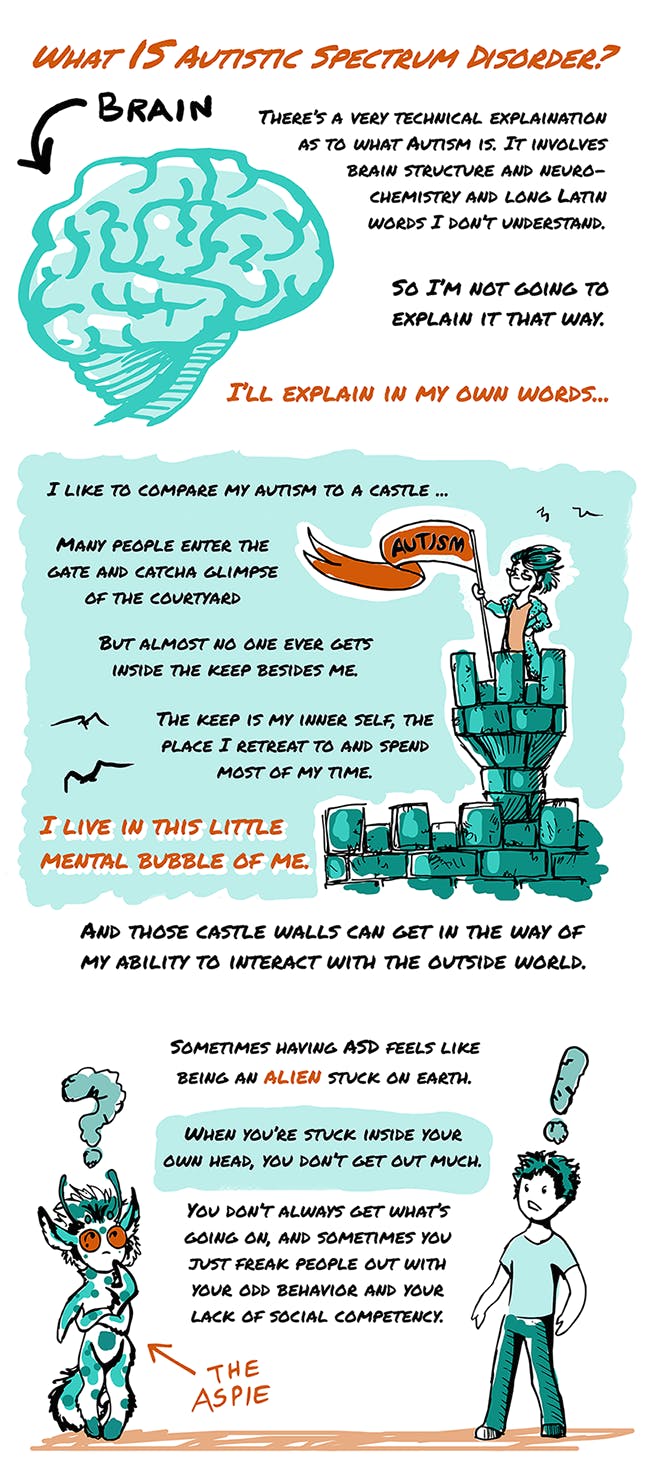

Asperger’s syndrome is a mild disorder that’s part of a larger group of developmental disorders called autism spectrum disorders (ASD), according to the site Autism Speaks. Before the latest iteration of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)—the guide psychologists and social workers use to diagnose people with mental disorders—Asperger’s syndrome was its own diagnosis. The DSM-V, however, folded Asperger’s in with autism and some other developmental disorders under the umbrella category ASD.

In general, ASD are poorly understood by pretty much everyone—the public, doctors, researchers, and schools. Like the name suggests, people who have ASD fall along a spectrum varying in both severity and symptoms. Some people with very severe autism are totally unable to communicate verbally and have severe developmental disabilities. Others, such as those with Asperger’s syndrome, are quite articulate and sociable, but still face many challenges in everyday life. Given the diversity, some people, like Hughes, choose to identify with their specific diagnosis as well as with ASD in general. Scientists are learning more about how the ASD works and what may cause it every day, but much about the disorders remain a mystery.

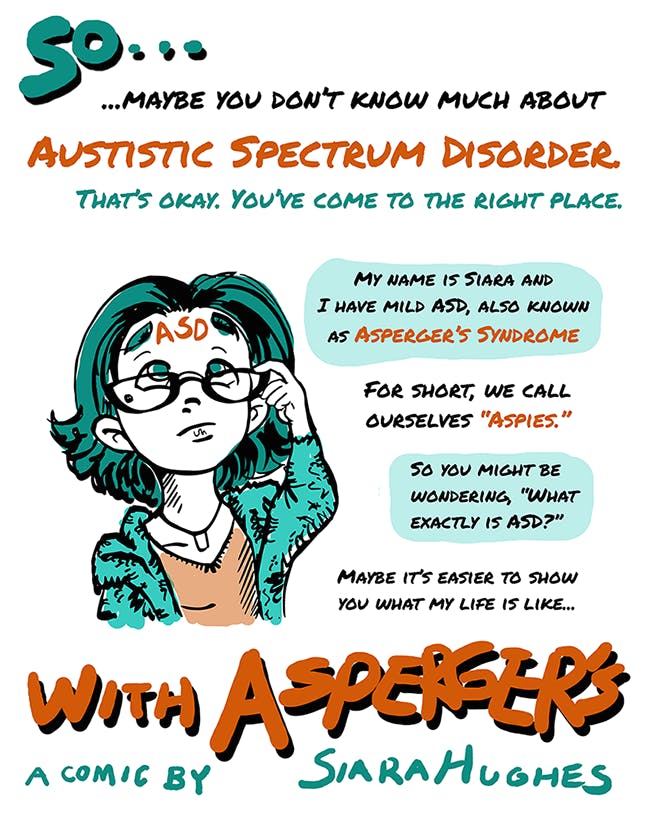

With so much misunderstanding of her condition, Hughes decided to demystify ASD using her own experiences and talents for comic art:

Hughes’ comic appears on the site Deviant Art, where she posted under the name OnTheMountaintop. She is currently studying for a degree in graphic design and visual communication, explaining:

“I started this [comic] as my final project for 2D design last quarter and I just finished it yesterday while I had free time to work during my printshop internship. This comic is the culmination of dozens of hours of work, lots of frustration, a couple of tears, and an earnest desire to explain myself to other people.”

Hughes diagnosed herself after reading about an autistic character in a book, and then doing some research, she told the Daily Dot. Her younger brother was recently diagnosed with ASD, she continued, and she began to see some troubles in his life that reflected her own. “I went through most of my life without knowing [about Asperger’s syndrome],” Hughes, who is 21, said. “I did a bunch of research and I found that all of these little quirks that I’ve written off were ‘a thing.’ It’s actually a recognized set of [symptoms] that other people have.”

People with Asperger’s syndrome might display repetitive behaviors, a very deep interest in just a few areas, and strange or inappropriate social behaviors, according to Autism Speaks. They may also have trouble reading nonverbal cues like body language and eye contact.

Researchers are still looking into what causes ASD. A family history seems to be a strong risk factor, suggesting that genetics are at play. There is also evidence that a woman getting sick during pregnancy, prompting an immune response, may also play a role. Having children at an older age also ups the risk. For some people with severe forms of autism, parents may notice signs as early as 18 months. Some of the signs include delayed milestones, like speaking, and a lack of eye contact. Other people with ASD will progress normally but then “regress” around age two or three. As was the case with Hughes, some people are not aware they have an ASD until they are older.

Researchers are also looking at the brains of people with ASD and finding that they contain more synapses—connections between brain cells—than most in certain areas. Other parts of the brain, on the other hand, show fewer synapses. This probably comes into play with some of the behavioral symptoms of ASD, but it’s unclear how at this point. Eventually, understanding the neuroscience underlying ASD may lead to better treatments. Many people with Asperger’s syndrome respond well to cognitive behavioral therapy, which helps people develop new behaviors to help deal with social situations.

While connecting with others comes naturally to most people, Hughes approaches socializing in a more analytical way. “If I’m going to understand someone else and befriend them and interact in a positive way, I need to get inside their psyche and understand what’s going on under there,” she said. “That’s interesting coming from a person with zero social skills. I want to be able to communicate, I want to be able to understand people, and it means I have to learn how to do it.”

Sometimes Hughes has moments that are hard for others to understand. For example, she sometimes has trouble controlling her emotions when she feels overwhelmed by overstimulation—particularly in the form of light, heat, touch, or unfulfilled expectations.

Researchers are also not clear why some people with ASD are so sensitive to certain stimuli. Some people can only wear certain fabrics because others feel unbearably scratchy, while other people have difficult times with loud noises or crowded rooms. The sensitivity is linked to how people process different senses, researchers believe, and that processing ability is impaired in people with ASD. According to the National Autistic Society of the UK, hypersensitivity to different senses may lead to anxiety or behavioral issues in people with ASD.

Touching is a big trigger for Hughes. If someone hugs her unexpectedly, she said, she may feel as though their arms are still around her long after the embrace is over. And sometimes this overstimulation leads to what she calls a “meltdown.”

Naturally, these meltdowns—which may occur in public—are extremely stressful for Hughes. “The meltdowns don’t happen on cue. I don’t will them to happen; I will them not to happen. I don’t like falling apart in public,” she said. She added that she’s gotten better at avoiding having meltdowns, but that in the past it didn’t take much to trigger them. “Sometimes changes are so emotionally impactful, even small changes,” she explained. “Every time the library system would update their catalog, I used to lose it because I couldn’t handle the changes.”

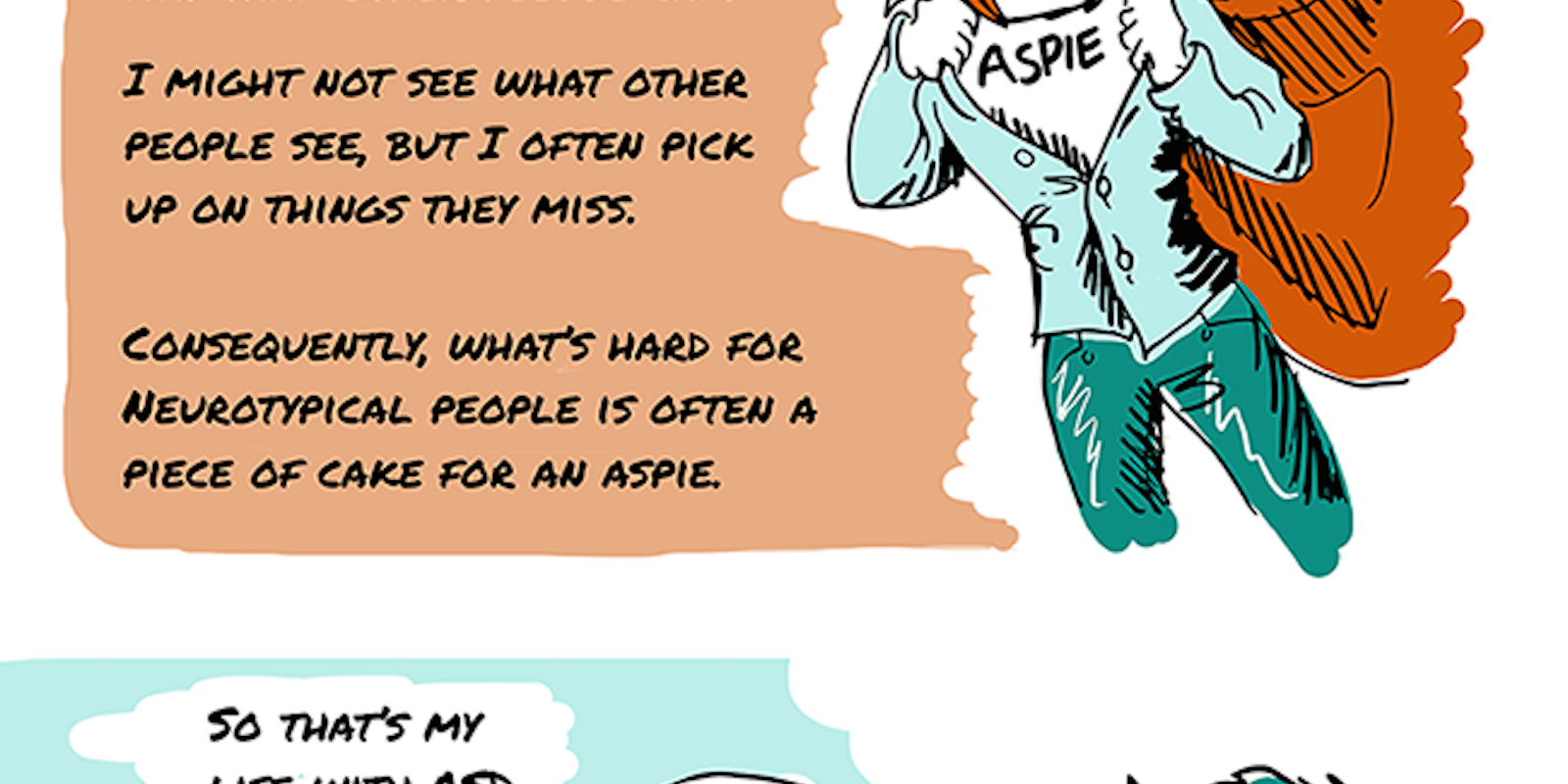

Yet like many other people with ASD, Hughes wouldn’t change her brain for the world. The flipside to Asperger’s, for her, is that she sees the world in a different way than most “neurotypical” people. She has an inquisitive mind and a capacity to deeply immerse herself in topics she finds interesting.

Hughes hopes her story will others who might not know anyone with ASD—or may think they don’t know anyone with ASD—understand that not everyone thinks the same way they do, and that’s just fine.

Art and comic courtesy of Siara Hughes