Election time in Iran means increased censorship for the country’s tens of millions of Internet users. But this months parliamentary election, experts say, comes with a new level of aggressive censorship from a government notorious for authoritarianism in cyberspace.

“What’s happening [right now] is far more advanced than anything we’ve seen before,” said Karl Kathuria, CEO of Psiphon Inc., the company behind the widely popular encryption and circumvention tool Psiphon. “It’s a lot more concentrated attempt to stop these services from working.”

Next to China, Iran is generally considered one of the world’s most heavily monitored and censored countries online. Censorship has been practiced in the country for over a decade, but ever since Internet activism helped spark the 2009 Green Protests, elections have been a hot spot of activism and, in turn, reactionary censorship in a country with an increasingly deep heritage of online advocacy.

“2009 was a big lesson in the mobilizing potentials of the internet,” Mahsa Alimardani, a researcher at the University of Amsterdam, told the Daily Dot. “So in 2013 they practiced throttling at sensitive moments—like when candidates were registering at the ministry of interior, etc.”

“There are attacks on our infrastructure all the time, they’ve become particularly acute over the past month or so.”

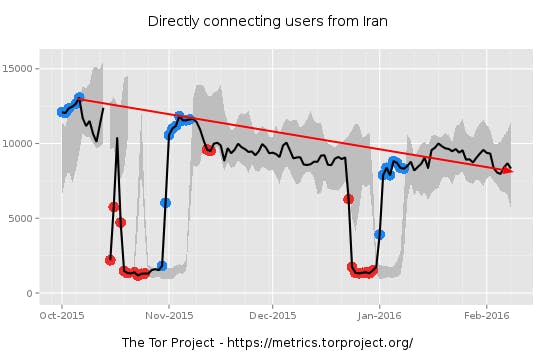

Many popular censorship-circumvention tools have in recent weeks seen a large drop in their connections from Iran, according to Nariman Gharib, an Iranian researcher and activist based in the United Kingdom. Tools like Psiphon and Tor, the world’s most popular anonymity network, have seen large fluctuations and drops in Iranian connections over recent months.

“There have been disruptions to services like ours in the last couple of months,” Kathuria said. “We’ve always kind of expected that would happen in the run up to the election.”

Psiphon has become popular across the Middle East largely through word of mouth. It’s been used in Iraq and is now a popular tool in neighboring Iran. Along with use of other tools like Tor, Psiphon activity serves as a bellwether of a broader offensive being waged from Tehran.

Kathuria recommends Iranian users experiencing difficulties connecting to Psiphon “go and get the software again” to obtain new updates. His team has released at least eight updates in the last month to counter the evolving Iranian disruptions.

Although this election is bringing on “more advanced” censorship action from Iran, Kathuria stresses that attacks against circumvention tools “happens regularly.”

“The message is to keep trying,” Kathuria said. “If people have problems, they should keep trying. We’re continually developing and doing what we can to keep them connected.”

The Tor connection

Tor developers too are not exactly being caught off guard, either. Later this month, they’ll be meeting in Spain. Because the Iranian election will take place at the same time, one of the long-suggested activities was to monitor Iranian disruptions and use it as a learning opportunity, according to early planning documents for the 2016 Tor developer’s meeting.

Despite its broad popularity, Tor is actually one of the less popular censorship circumvention tools used by Iranians for several reasons.

In addition to being aggressively targeted by government authorities, Tor also has a reputation of being excessively slow inside the country. Iran’s connection speeds are already often slow to start, and government authorities slow connections further as a means of censorship. Downloading and running a program like Tor is seen as impractical by many Iranians.

Tor developers did not respond to a request for comment.

In the last month, Gharib says, he’s received 198,000 emails requesting new proxy and circumvention tools in Iran, signaling increased difficulty in getting a free and clear connection from within the country. On Telegram, the most popular social network and messaging tool in Iran today, Gharib says he’s received 500,000 such requests.

This year’s parliamentary elections are a relatively small affair compared to the presidential contests of 2009 and 2013, making the government’s reaction seem disproportional.

“Most of the reformist candidates did not make the cut for the February elections,” Alimardani said, “which might mean there might not be that much excitement, as the exciting candidates have not made the cut.”

Even so, censorship is on the rise.

“There are attacks on our infrastructure all the time, they’ve become particularly acute over the past month or so,” Kathuria said. “The way we deal with that is, we divert as many resources as we can to keep our network stable and people connected.”

From Tehran to Telegram

In the last year, Telegram has become enormously popular within Iran, mirroring the app’s rise in the Middle East at large. Public institutions have embraced the social network, including Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei who boasts over 200,000 followers on his account. Well over 10 million Iranians are using Telegram, according to government officials. Various surveys of Iranian netizens place that number at 20 million or higher.

“If people have problems, they should keep trying.”

Telegram offers encrypted chat, a feature that is meant to keep out eavesdroppers like Iranian authorities. And Iran’s Internet watchdog recently publicly announced they would not be filtering the app, despite their propensity for filtering and outright banning networks like Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, and Viber.

The level of cooperation between Telegram and the Iranian government is not at all clear. Telegram CEO Pavel Durov denies any cooperation, but Iranian authorities have said that they’ve worked with the app’s developers on censoring explicit stickers and emojis and arranged for Telegram to store Iranian user data within the country. In addition, cybersecurity experts have criticized Telegram’s cryptography.

None of the experts interviewed for this story were quite sure of what’s happening between Iran and Telegram, but some prominent activists who are in danger of arrest due to their Internet activity in Iran have told the Daily Dot they can’t fully trust Telegram anymore due to the continued lack of clarity.

For most Iranians, though, Telegram remains the most popular choice for messaging, beating out even text messages and other apps.

Update 9:52am CT, Feb. 12: Added Mahsa Alimardani’s professional title.

Illustration by Jason Reed