Long before the autopsy, London police could guess what killed Yuri Gadyukin. When they pulled his body from the river beneath the Hammersmith Bridge on July 26, 1960, they saw a bullet-sized hole that had ripped apart his skull.

Authorities had been searching for the Russian director for weeks. By the time they yanked him from the Thames, they’d surely heard rumors percolating down through country’s film community of catastrophic arguments on the set of his latest film, The Graven Idol, between Gadyukin and the film’s star, Harry Weathers. Others whispered that Gadyukin owed money to a local gangster—cash he’d used to finance the film.

Perhaps you’ve heard of Gadyukin? He was a star of early Soviet cinema before fleeing to England. You can read about his life on a fansite and a Facebook group. You can watch him melt down in a British television interview, storming off stage in spittle-spewing rage. For nearly four years, there were Wikipedia and Internet Movie Database articles about him, brimming with citations from authoritative Russian sources.

Those entries are now gone. Yuri Gadyukin did not owe money to a gangster. His final film was not swirling out of control. Weathers did not kill him. His body was not found beneath the Hammersmith Bridge.

Gadyukin never died, in fact, because he never existed.

…

Imagine a documentary about events you’ve never heard of—that no one’s ever heard of—but that are meticulously chronicled in online sources many people trust implicitly. Imagine the confusion. Imagine the buzz. Imagine the publicity.

It’s almost sad that Wikipedians discovered the Yuri Gadyukin hoax on March 5 and ripped it from the encyclopedia like a noxious weed. The piece was not a work of trolldom. It was not a hoax for hoax’s sake, born of boredom and a passing interest in fucking things up on the Internet. Yuri Gadyukin had purpose. He had so much potential. He was born of exhaustion, beers, and Jorge Luis Borges. He could have (and still might) make two British filmmakers famous.

The hoax that fooled the largest encyclopedia and Internet movie database on the planet for nearly four years began when Gavin Boyter and Guy Ducker stumbled into a Belgian restaurant in London in 2002. They were tired. Boyter was an inexperienced director who would sometimes shoot reams of footage in a single day. Along with Ducker—who has editing credits on more than 20 films—he’d just passed the whole day cutting down footage for his first film, Anniversary.

The drinks and exhaustion sparked their imagination. They tossed out fantastic hypotheticals, wondering what kind of director would “shoot an insane amount of material, more material than anyone could ever watch,” as Ducker later recalled. “What kind of person would shoot an endless film, just never stop shooting?”

The two friends were forging a fascinating character—a fictional marriage of legendary Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky and control-freak geniuses like Stanley Kubrick, an archetypal director slowly creeping into madness. Or as Ducker described him, “a slightly psychotic person. And a slightly manipulative person.”

They were creating Yuri Gadyukin.

Thanks to busy work schedules, it would be years before they acted on the idea. But by 2005 they had a script, a faux documentary-cum-murder mystery that would follow a hot young British filmmaker as he reconstructed the lost footage of Gadyukin’s final, unfinished film. As he digs into the movie’s seemingly endless mountain of film reels, he begins to unravel the threads of Gadyukin’s last days—and finds himself ensnared in an ongoing mystery around his death. There’s too much film, he realizes: Someone must still be shooting the movie.

Gadyukin left behind seemingly endless mountains of film reels.

Photo via Guy Ducker

Their picture would be equal parts The Blair Witch Project and The Usual Suspects. They called it Nitrate, after the literally explosive film stock Gadyukin used.

With a script, Boyter and Ducker had to tackle a more difficult problem: How could they convince studios to dump cash into an indie project with a complex plot and no obvious mass market appeal? Their solution was brilliant and even a little insidious: They would start telling the film’s story before a single shot had ever been made, before a single actor had ever been cast.

They would make their fictional world a reality on the Internet.

…

In the Jorge Luis Borges short story “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis,” a researcher uncovers a conspiracy of intellectuals who have forged an entirely fictional universe by writing encyclopedia entries about it. The piece seems eerily prescient in the Wikipedia era, in which the biggest and most used encyclopedia on the planet is the collaborative product of millions of strangers. Anyone can write anything about anybody.

A newspaper clipping from the day Gadyukin’s body was found.

Boyter and Ducker (both fans of that Borges story) took advantage of Wikipedia’s malleability to create their own encyclopedia conspiracy. On August 3, 2009, they made the Yuri Gadyukin Wikipedia page.

That page became an anchor for what they planned to be a years-long viral promotion campaign. The main character in their online plot would be Leonard Brabkin, a fictional middle-aged Kentucky author (and the only thing close to a Gadyukin expert) who was working on a book about great lost films. Brabkin had no role in the movie’s script, but he was key in blurring the line between reality and fiction online.

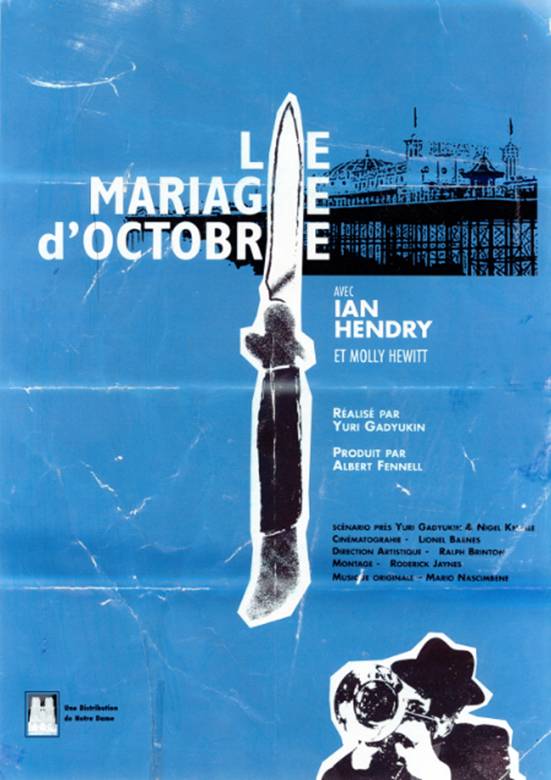

Boyter and Ducker used Brabkin to create Gadyukin’s fan site and Facebook page. Across the Internet, Brabkin dropped tantalizing hints of Gadyukin’s real existence, including stills from his movies and newspaper clippings reporting his death.

Friends helped out, too. On Gadyukin’s Facebook page, dozens of apparent strangers littered the thing with made-up memories about watching his films. “I’m sure Channel 4 showed Where The Tractors Roam very late one night when I was about eight years old,” one wrote. “Are any of these now available on DVD?” And everywhere—Facebook, YouTube, blog comments—Brabkin was always there, dropping comments, pushing the conversation, making it seem real.

Through another phony account, the pair posted an outtake from a British television interview where Gadyukin melts down and leaves the stage in a fit of rage.

Another friend of Boyter and Ducker who ran a film blog took the hoax even further. On the day before Halloween in 2009, he described a weekend incapacitated by sickness, watching Gadyukin classics “on a pair of battered and deeply treasured VHS cassettes which date back to the late 1980s when my Mum taped two of Gadyukin’s films which were screening very late one night on BBC 2.”

The campaign was so convincing that Gadyukin almost jumped off the Internet and into real life. In November, a self-described “occasional visiting director” of an acting school in London reached out to the blog’s author. He was directing a play about Gadyukin, “but information is really sparse on the web,” he wrote. “I’m still waiting to hear back from Leonard Brabkin, but really need to get some pointers on where I can glean some more information.”

Here was a chance to take the hoax to another level entirely, to make Gadyukin so real that people would be talking about him, that an actor would actually play him in a fictional biography of his life. But when Boyter and Ducker reached out to the hopeful director, it was to tell him the truth. To do otherwise, Ducker said, would be to turn the hoax “into a lie.”

Still, they couldn’t help but feel satisfied. Their odd plot was working. To people who had stumbled across Leonard Brabkin’s Internet trail, Yuri Gadyukin was very real.

A promotional poster for Gadyukin’s The October Wedding

Viral marketing campaigns are hardly new. The concept goes at least as far back as The Blair Witch Project, the 1999 horror film and faux documentary. Directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez loaded a website with video clips and supposedly real journal entries left behind by a team of filmmakers who’d gone missing in the Maryland woods, adding the film an unnerving sense of reality. Since then, most viral campaigns have been less interested in blurring reality than with building buzz. In most cases, “viral” is little more than a synonym for “advertising on the Internet.”

There are a few exceptions. J.J. Abrams’ Cloverfield had an intensive viral campaign of phony websites and blogs from characters that added new facets to the story entirely. But the film was a sci-fi blockbuster about a giant monster attacking New York. Anyone who stumbled across those viral clues could guess pretty quickly that it was all fake. The 2012 indie film Sound of My Voice, about a Los Angeles cult, took viral promotion to a new level entirely when it organized weekly public meetups at L.A.’s Ukrainian Cultural Center. Actors would show up in character, then talk religion with any stranger who showed up.

Few viral campaigns actually try to alter your perception of a film’s story before the audience watches a single scene. Nitrate was special because its creators were playing the long game. Boyter and Ducker knew it might be years before they shot a single scene. By the time a real promotional campaign was ready, the pages would have existed so long they’d have gained weighty authority just by dint of their age.

…

Ducker and Boyter probably never expected their devious plot would be spoiled by a single Wikipedian. His name is Yaroslav Blanter. He’s a Russian nanoscientist who teaches at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. Blanter is a long-standing Wikipedian who specializes in Russian-language pages, even obscure ones like Gadyukin’s. When Blanter decided to check the sources on the Gadyukin article, it was all over.

Blanter explained his solid case March 5 in a post nominating the Gadyukin page for deletion:

A blatant hoax, and seems to be one of the longest-living hoaxes we have. None of the sources exist. The [search] in Russian (Юрий Гадюкин) does not give anything at all. The name (Gadyukin) is a made-up family name used by Yury Iosifovich Koval Viktor Dragunsky in one of the children’s stories (Death of the spy Gadyukin). The alleged name of the first movie, Where the tractors roam, sounds so funny in Russian that it just could not have been shot in the 1950s.”

After a few concurring votes from fellow Wikipedia editors, the page was gone. And soon Wikipedians had dug up another hoax article by Ducker and Boyter—something called the Bucharest Film Festival, a key part of Gadyukin’s career, where he had won a major award.

Now, both articles are gone, their subjects relegated once more to fiction. The only proof of their existence is a mention on Wikipedia’s list of longest hoaxes, where they share the dubious company of a 17th century Indian war that never existed and an assassin of Julius Caesar who never lived.

…

It’s been more than 10 years since Boyter and Ducker created Yuri Gadyukin over too many beers at that London Belgian restaurant. The hoax has been discovered, ripped out of WIkipedia, and now reported here in this story. The game is over. But they’re not close to getting discouraged. If anything, things are starting to pick up.

Boyter and Ducker are still playing the long game.

In 2009, they brought on a producer, Christine Hartland, who has some experience working on faux documentaries. They made a trailer that year as well.

Earlier this year, the slowly growing team cast their first actress, Lucy Davis, best known to American audiences as Dawn Tinsley in the British version of The Office.

The viral campaign was “a way of us starting to tell a story, starting to create the world,” Ducker said. “While in the meantime we waited for people to give us the money. We were determined not be to be stopped from getting that. You have to make sure nobody stops you. That’s the key to making a film.”

Hartland is working feverishly to raise money. She wants the film to be in pre-production in early 2014.

In the meantime, be careful when you stumble upon fascinating truths spun on the Web. You might unknowingly be playing a role in the next great indie film campaign. And if you ever run across a Leonard Brabkin, don’t believe a thing he tells you.