With your help, and some space age camera-work, Oxford University may be on the verge of translating the world’s oldest writing system. Using both the latest imaging technology and the practice of crowdsourcing, scholars there hope to soon decode the language and a brighter light on an ancient world.

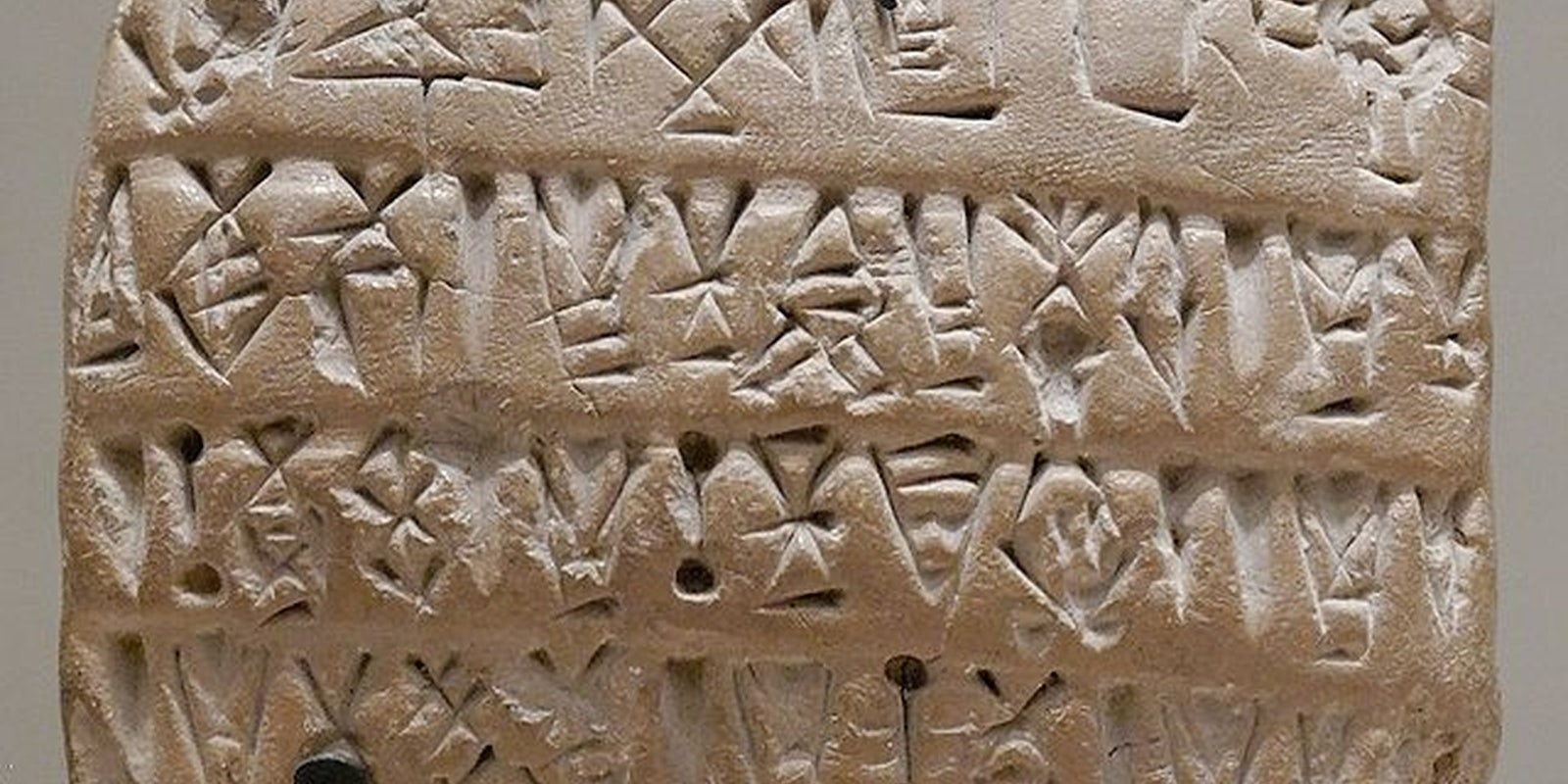

Proto-Elamite, as the language is known, is a 5,000-year-old Bronze Age writing system (which may or may not have reflected a spoken language) from southwest Iran, whose unusual symbols have been a mystery to epigraphers and other scholars since its discovery.

Imaging

Led by Dr. Jacob Dahl, fellow of Oxford University’s Wolfson College and director of the Ancient World Research Cluster, the imaging part of the project centers on the Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) System, an imaging system with 76 different lights and a processing software. First, Dahl’s team photographed proto-Elamite at the Louvre museum in Paris, which has the greatest collection of clay tablets containing the language.

Globally, there are about 1,600 tablets, fragments and texts containing the language, which were found at the old Elamite, and later Persian, capital of Susa and at other locations in southwest Iran.

Dahl also photographed tablets at Oxford University’s Ashmolean Museum.

The RTI system is a black dome, inside of which are 76 different lights and, at the apex, a high-resolution camera. Operators take 76 separate pictures of each text, one under each of the 76 lights. Those images are then processed into one three-dimensional image that reveals the slightest nick and notch and can be turned around 360 degrees in virtual space, to be looked at from any angle. The differences in quality and intensity of the different lights can be adjusted within the image to bring out light and shadow that can lead to a clearer understanding of a symbol.

To date, the scholar has translated about 1,200 proto-Elamite symbols, including their numbering system, but the language as a whole, as an integrated system, remains out of reach. The reason for this persistent elusiveness, he told the BBC, was the lack of contemporaneous scholarship, with no word lists or scholarly scribal exercises ever found for the language.

“It’s an early example of a technology being lost, The lack of a scholarly tradition meant that a lot of mistakes were made and the writing system may eventually have become useless.”

Another reason for the difficulty is the absence of bilingual texts. The Rosetta Stone, the key to the deciphering of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics is one of the best examples of a multilingual text. Containing Greek, Demotic Egyptian and hieroglyphics, the cross references between the languages led to its eventual decoding by Jean-François Champollion.

Crowdsourcing

Dahl hopes to enlist the help of scholars and scientists, as well as interested laypeople, across the world to help in comparing and deciphering the remaining symbols. To that end, he has launched a wiki for interested contributors, connected to UCLA’s Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative. He has also published an email address, cdli.oxford@orinst.ox.ac.uk, for contributors to reach the project.

Anyone wishing to be part of a new Rosetta Stone moment might want to look into how they might contribute to the effort.

The historical importance of proto-Elamite lies in its example of one people borrowing writing from another, in this case from the people of Mesopotamia. But even with the loan words as a guide, the meaning of 80-90 percent of the symbols remains unknown,

Besides, as Dahl told Sci-News, the writing from this part of the world and this era, “contains the first substantial law code, the first record of a battle between kings, the first propaganda, and the first literature.”

So far, Dahl and others have figured out that the land of the proto-Elamites was an agricultural one, with a large workforce subsisting on little food, mostly barley and small beer. The middle and upper classes had meat from sheep and goats, yogurt and honey. On all the tablets collected, there are depictions of animals, both real and make-believe, but none of human figures, not even, as the BBC notes, an eye or hand.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons